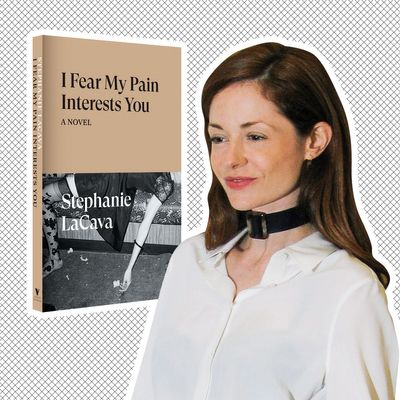

Stephanie LaCava approaches her second novel, I Fear My Pain Interests You, as the next logical step beyond our obsession with a sad-girl world. The kind of dissociative feminism she skewers is a well-documented media phenomenon — from the breaking of the fourth wall in Fleabag to Ottessa Moshfegh’s writing. LaCava’s protagonist, Margot, cannot feel any physical pain, a particular character trait that brings to mind an essay by Leslie Jamison titled “Grand Unified Theory of Female Pain.”

Jamison asks, “How do we represent female pain without producing a culture in which this pain has been fetishized to the point of fantasy or imperative?” Women’s experiences of pain, she argues, have undergone a historical cycle of romanticization and rejection; Anna Karenina throwing herself in front of a train or Blanche DuBois’s cries for love were once literary wounds illuminated by adoring audiences, but we now scoff at the melodrama of a woman (Hannah Horvath in Girls, for example) daring to express how much she’s hurting. Rejection has led to dissociation, deadpan quips about heartbreak, eating disorders, or the torment of mental illnesses, and “cool girl” unfeelingness in order to never again be associated with such hysteria.

But how can we do as Jamison asks and move beyond what is becoming a played-out examination of the female condition? In LaCava’s book, her protagonist could easily be read as a conventionally damaged heroine — lonely, stuck in relationships with older men who treat her poorly, distanced from her difficult and famous family. As Margot finds herself fleeing New York City for the quiet solitude of Montana, she meets a man known only as Graves, whose fascination for her ultimately enables her independent reclamation of herself. Her inability to feel pain (stemming from a condition called congenital analgesia), rewrites what it means to be a “suffering” woman. Rather than further suggesting distance and aloofness like the cool-girl trope, LaCava inverts this concept to lift Margot away from the trappings of commodification. Her pain, or lack thereof, may interest you, but you won’t be able to enjoy it.

Where did this book and the character of Margot originate for you?

I originally found a clipping about congenital analgesia from a study that was done at the Salk Institute about ten years ago and I had saved it. I can still see the image of the girl from the article, and I remember knowing that I wanted to use it somewhere, but I wasn’t really sure how. In the time between then and now, I’d seen other things written about it. It stuck with me as something I wanted to use, in a surrealist way.

Margot’s voice within the book as well as the structural choices you make — the nonlinearity, the overlapping narratives — create a really immersive experience. Was this an important feeling for you while writing?

Visceral, immersive. I like to use the word haptic. It’s this feeling of the in-betweens and the absence in the spaces. There’s a lot of negative space that affirms itself by being so negative: The book is about pain, but it’s also about no pain. A lot of my writing is also about the psychology of relationships and realizing the unseen, untold things that make us have unconscious reactions. Some people immediately associate this with a kind of dissociative feminism or “sad girl style” or whatever. I actually think it’s the thing after that. That is an “outside in” approach and I’m more “inside out.” Sure, it sounds aloof and detached, but I’m using it to go into the viscera. I link into the sad-girl thing in my interest in the young woman as this highly dangerous, inflammatory, very marketable cipher within these systems of the world. That’s what I’m interested in exploring as a cultural industry phenomenon, more than just saying, “Oh, this is a book about a sad girl.” For me, this is the next step from there.

That’s a phenomenon I’ve grown up with and absorbed from my cultural consumption, particularly on a platform like Tumblr as a teenager. It was Lux Lisbon from The Virgin Suicides, or the characters from Skins, or any number of other sad girls who were positioned as incredibly aspirational.

I’m so interested in using that style for the purpose of inverting it and looking at it from the inside out. The aloofness is a way of combating my own emotionality, but I think that comes through in the story between the lines. I mean, the book isn’t cold. Everyone who reads it has some kind of discomforting sensation, and any kind of sensation must therefore counteract coldness.

I also think of Virginie Despentes, and Zoë Lund in Abel Ferrara’s Ms. .45, which gained a cult following — also related to the Tumblr aesthetic. Ms. .45 has that image of Lund with the big red lips dressed as a nun and the gun, and there’s a certain number of girls of a certain generation who have been that for Halloween! This aesthetic represents this idea of imagery infiltrating our consciousness. That’s all part of the same systems, happening at different times in different ways, but all at once.

I think it also speaks a lot to the ways in which women’s trauma and pain, in youth in particular, is commodified. Margot’s vulnerability, and her inability to feel pain, is a kind of spectacle for the men around her.

In Margot’s story, there is no redemption. She doesn’t find exactly what she’s looking for. But there’s a larger message and a subtle political narrative in the book that’s really important to me. It’s about admitting that this is the world that she inhabits. It’s full of compromises and contradictions for young women, but a better world is possible. The better world is not the one she’s living in, not the one we live in. It’s something else. That’s very sad, but not “sad girl” in the sense of indulging in one’s sadness. It’s just more, I don’t know, nihilist? Without spoiling the ending, Margot does take back the story. Even if it’s just in one line, the taking back of the narrative is a real thing.

The book also explores Margot’s life as a “nepotism baby.” It seems to be a comment on the contemporary rise of celebrity children on TikTok or Instagram and their power as young influencers or “It” girls. It feels connected to what we’ve been talking about with that Tumblr aesthetic, but also asks broader questions about privilege and wealth.

Nothing in the book is a direct hit on anything, but I’m curious about connection or disconnection dynamics. In the beginning, this was more about getting to the crux of this idea — that I’ve seen for both men and women — of partnering with the child of something you wish to become. Whether it’s by merging with the person physically or subconsciously wanting access to their connections, being part of the family then means you’re part of a legacy. You can create a legacy for yourself that never really existed as a way of creating identity, as a way of being grounded in something. But this is a critique, not an endorsement.

Someone may say Margot has many privileges, but they’re looking at what she can get them and how she can make them feel about themselves. She’s not “free” — in a nontraditional sense, she’s unable to connect with herself.

You mentioned the structure of the book earlier and it starts in the air, in a plane, and it ends very close to the earth, at a gravesite. She flees the city, where she’s known her roots to be, to go to this far-off place. She’s always locked in because of the family she has, the systems she lives in, and because of what’s happened to her. It’s ironic, too, because her parents are supposedly these punks — but she’s trapped in this very bourgeois setup. It’s clear she’s not punk. Her family has given her all these things that check someone’s boxes, but that she wants no part of. It’s not about pitying her; it’s about looking at the systems and configurations that leave Margot so numb.

I saw you post on Instagram about Geraldine Leigh Chaplin. Was she the nepo-baby inspiration for the novel?

She’s the consummate example. Her mother was the daughter of Eugene O’Neill, her father was Charlie Chaplin. She’s got literature on one shoulder, cinema on the other, she’s incredibly beautiful and talented. There’s a lot in the book between the lines about genetic inheritance, and disease, in Margot’s case.

The canceled Cannes Film Festival of 1968 is really important to the story, and she was there with her film Peppermint Frappé, which she made with her husband at the time. The story goes that they clung to the curtain during the festival to make sure the film didn’t get screened. All of these things are just so interesting to look at. It’s funny you mentioned The Virgin Suicides earlier and Sofia Coppola, another nepotism example a generation later.

In relation to Margot’s disorder and her numbness, the book has a strong relationship to the body-horror genre, or the French cinema du corps. There are also clear parallels to David Cronenberg’s recently released Crimes of the Future — were you intentionally trying to make those connections when writing the book?

The “sex is the new surgery” tagline in Crimes couldn’t be more perfect! But it does show that there’s a reason why these things happen, the pushing forward of an idea or a critique of the culture industry, or of the world as it stands, and the politics of the moment. The cinema du corps was a huge influence on the entire book. I thought a lot about Gaspar Noé’s Irreversible, or Julia Ducournau’s Raw, which is actually called Grave in French, and Claire Denis’s Trouble Every Day. Denis often works with a novelist, and they leave gaps that allow the audience to project something onto the film. All of that influenced the story, as well as the subtle politics of Denis’s films. There’s also Marina de Van and Catherine Breillat — a lot of them are female filmmakers making these kinds of works where sex is always a factor, but then the body is always a factor. There’s often a young woman navigating that. All of that is a blueprint for I Fear My Pain Interests You.