From the ages of 7 to 9, I was frenemies with a girl who had it all: a pink Motorola Razr, a closet full of Limited Too, and minimal adult supervision. We were frequently left to our own devices in her dad’s condo under the watchful eye of her miniature Maltipoo, Gucci. Our friendship wasn’t made to last — a series of escalating arguments reached a boiling point when she called me fugly and I kicked her in the stomach. In our time spent together, I can really only recall one instance we didn’t bicker: the day we huddled around her laptop to learn the Soulja Boy dance.

The continuing popularity of “Crank That” and scores of replica videos earned this choreography its place in the pantheon of sleepover dances — the silly, watered-down routines that often come together during the wee, giggly hours of a slumber party. Every era is marked by its own sleepover dances, from soft choreo to the Spice Girls to learning the “Say So” routine on TikTok, but the experience is a girlhood rite of passage. For some, it doesn’t stop at puberty. Earlier this year, when the Haim sisters debuted a mid-song dance break complete with arm circles and stone-cold expressions, fans were vexed by its earnest mediocrity. What seemed to make people so uncomfortable was that the dance was reminiscent of the routines that children perform for a captive adult audience, still too young to feel the sting of embarrassment. As one person wrote: “I love that Haim’s whole thing is just ‘what if you never stopped putting on shows in the living room with your cousins.’”

We demand a level of finesse from performers, lest they fall victim to vicious memes à la Dua Lipa. Onscreen, however, dance numbers fail when they demand the audience suspend their disbelief and accept that a Broadway-caliber number fits organically into the plot (one exception to the rule being the tragically canceled Bunheads). This isn’t to say that dance has no realistic place in television — just the opposite. Time and time again, the sleepover dance has proven a perfect vehicle for plot, wordlessly conveying tension, nostalgia, and platonic love within deeply literal eight counts.

The sleepover dance is a time machine to childhood. At some point, self-seriousness eclipses joy and we stop inventing dances with our friends. Not only do we lose an unparalleled bonding activity, but our sense of selflessness dwindles too. “When people dance together in a synchronized way, then that prosocial behavior goes up,” says Dr. Peter Lovatt, founder of the Dance Psychology Lab and author of The Dance Cure. Group dance, no matter how basic, promotes a spirit of togetherness. “What’s extraordinary is that when you’re dancing with other people, you think, Oh, this is just a fun thing, we’re getting groovy together,” Lovatt says. “But actually, that sense of getting groovy together is changing all kinds of things. It’s changing how much you like each other, how much you trust each other, the similarity between each other, and how much you’re prepared to help one another.”

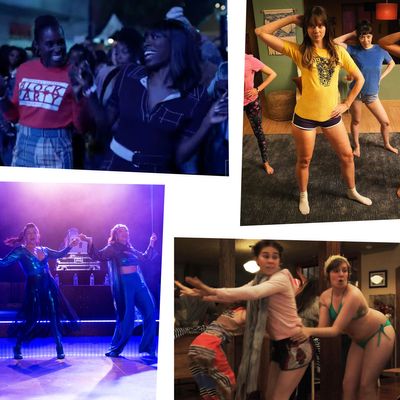

On television, group choreography scenes shine when they clarify the many complexities of our relationships. Perhaps an extension of childhood itself, the trope succeeds in illustrating the ebb and flow of old friendships as they enter adulthood. In the fourth season of Insecure, best friends Issa and Molly are in the midst of a falling out when a block party rendition of the wobble brings them back together — even if just momentarily. Despite Issa’s initial reluctance, she eventually joins in, and the two share a brief reconciliation. The dance isn’t just representative of time lost but people lost, too. In season two of Reservation Dogs, after the Aunties (minus Cookie, who died years earlier) perform childhood choreography to Brandy’s “Sitting Up in My Room” at a conference, Rita asks the group, “Y’all ever feel like we just went from kids to being women overnight?”

The sleepover dance is just as potent in the dissolution of fraught relationships, too, and can often emphasize the heartbreak of disintegrating childhood friendships. In the television adaptation of Everything I Know About Love, choreography to Little Dragon’s “Ritual Union” becomes a battleground when a petulant Maggie refuses to perform the dance for Birdie’s new boyfriend. Sure, it’s a dumb hill to die on, but for Maggie, the dance is representative of her shared history with Birdie and her fear of losing her best friend to her new relationship. Letting a newcomer in on an old ritual isn’t only sacrilegious, it’s a clear act of demotion in her best friend’s life.

Ultimately, the dances we create as children can be lifelong tethers to people we lose common ground with over time. One of the most memorable episodes of Girls is season three’s “Beach House,” where a trip to the North Fork exacerbates the cracks in the friend group’s foundation. Sandwiched between the many wounds that reopen over the course of the weekend is a dance to Harry Nilsson’s “You’re Breakin’ My Heart,” which is also the catalyst for a massive implosion. Yet while many people remember the beach house blowout, fewer may recall the end of the episode, when the four emotionally exhausted women silently recreate the routine at the train station.

Though the friend group’s deep-seated issues certainly aren’t resolved by their routine, the episode is a master class in underscoring the innate love and history that the women share with one another. The use of soft choreography as a salve isn’t a cheap plot device, it’s backed by science. “People report trusting the other people they’re dancing with more. They feel more psychologically similar to one another,” says Lovatt. This phenomenon is thanks to brainwave synchronization that occurs when people dance in a group, promoting empathy and trust. “Because your trust levels and similarity levels have gone up and the liking has increased, then you have that sense of bonding,” Lovatt explains.

As a former ballet dancer, my relationship with dance was more often a modality for perfectionism than it was about having fun. But thanks to the pandemic and a reluctant TikTok download, I was able to lean back into the childlike joy of the sleepover dance. I often think back to a night my roommates and I spent hours learning the (deceptively simple) choreography to “Blinding Lights.” Just a week or so into lockdown, as others pivoted to hyperindividualism, we united to learn a 15-second routine. When I look back at the video, I watch as we miss counts and flail our limbs with dumb grins plastered on our faces with tenderness, and I’m reminded of Hannah Horvath, who perhaps captured the ethos of the sleepover dance best: “Why does everything have to be perfect? Like, it had a lot of spirit.”