“I think I’ll write a book about sex,” my mother, 76, announced on the phone one day recently.

“Really?”

“I’ve learned a few things. I know lots of tricks for when you want to make the magic last — or for when you just need to get it over with because you’re not in the mood or you have other things to do.”

I laughed. “You probably have a wealth of knowledge in that arena.”

“I wouldn’t go that far,” she snapped. I’d found the edge, the hint of a boundary.

My mom was never like the other mothers in the playground. She had a job and wasn’t interested in domesticity. I was raised on Cosmopolitan, Jackie Collins novels, and a merry-go-round of her men.

Growing up in Australia, she’d had dreams of medical school, but instead she had me at 22; she and my father had already broken up by the time I was born. So it was just me and my mom, until it wasn’t. Which happened often.

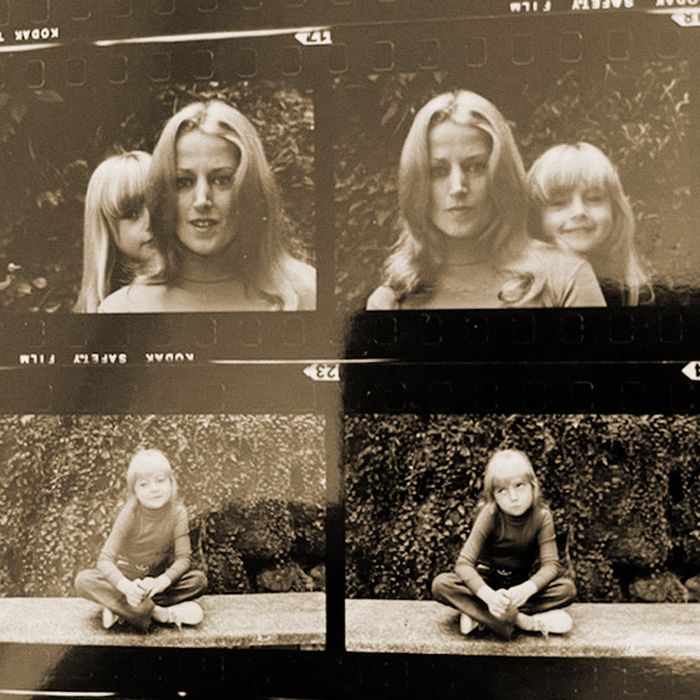

In grainy photos of my 20-something mother, she’s a slim bombshell with platinum-blonde hair, looking glamorous in a bikini with me as a toddler attached to her hip. She was never single for long. I learned early that having men desire you gave you a certain currency.

When I was 4, we moved from Australia to Hong Kong with her then-fiancé. When we arrived, we stayed in a hotel that overlooked the famous harbor. I remember falling asleep to the twinkling lights and waking to the sounds of them having sex — beside me in the same bed. The sounds they made frightened me, and I cried out for him to stop, thinking he was murdering her. They laughed, as if I were being silly, and brushed it off. I hated having to share my mother, especially in that way, but I also didn’t get a vote. Her fiancé had a temper and a crackling energy under the surface that made me uneasy. I tiptoed around him. That wasn’t the last time I witnessed or overheard her sleeping with a man, but in the years to come, when we often shared a bed, I would pretend to be asleep.

The three of us moved into a nice apartment with my own room. But after only a couple of months, they abruptly broke up, and we left. Back then, I didn’t know why they split, but I asked her about it this year, and she told me he had dragged her by her hair to force her to watch a television show with him. He also demanded she pay him back for a doll’s crib he’d bought as a gift for me. His fury was intensifying, so we moved out. All of a sudden, we were crashing in a crowded apartment with the only other people my mother knew in town. Later, we rented a grimy room in the red-light district, where we stacked our suitcases against the door to prevent intruders. Eventually, we found an apartment, and I started school, while my mother spent long hours at her job as a secretary.

“Didn’t you want to get married back then?” I asked her recently.

“It didn’t even occur to me,” she answered. “It was far too early in the game for that. I was still learning and observing.”

Without a dad or siblings, I was tethered to her for survival. We held hands everywhere we went, and I tried to make her laugh, to make her love me. I twirled around the living room and performed for an audience of one. I wanted to be enough for her so she wouldn’t need anyone else. She called me her “little mouse,” probably because I was a shy child who didn’t want to make waves. I never objected to that pet name until I grew up and an acting teacher screamed at me onstage, “What are you? A fucking mouse?” The teacher was so frustrated that I had zero physical presence, no sense of myself. I cowered in humiliation, and then it dawned on me: I had morphed into a fucking mouse.

There were mornings I woke up to discover my mother hadn’t come home, and that felt like a stinging betrayal. Why wasn’t I enough for her? We were a team. Why did she need to look elsewhere? But men offered something unquantifiable that I couldn’t compete with. During a move a few years back, I found school notebooks from when I was 7. One drawing stood out. It was of a girl with yellow hair in a big bed alone with the caption: “Mummy has gone out for the evening.”

When I was 9, I got a sibling. My mother fell in love with an American businessman and had a baby boy. Unlike me, this baby was planned. The father-to-be was generous and sent me big boxes filled with toys and clothes, and I was excited at the prospect of having a dad who knew exactly what clothes 9-year-old girls want. Unfortunately, it turned out he was married with daughters of his own back home. It was unclear when my mom knew that, but nonetheless, we weren’t becoming a family after all.

When my brother was around 4 and I was 13, we were sent to Sydney to spend the Christmas holidays with my grandmother. But we didn’t return, as planned. Without my being aware of it, I’d moved to Sydney. I felt like a piece of luggage that was shipped off and dumped with relatives — first with my grandmother, then my aunt, then my uncle — forced to change schools in the middle of the year in a completely different country. At one point, I dropped out of school for a bit; at another, I moved in with my best friend’s family. After nearly a year of not seeing her, my mother showed up with a boyfriend for a surprise weekend visit. When she saw me for the first time, I watched her scan my body and registered her disapproval. “You always need to be in good nick,” she said, using Australian slang for impressive conditioning, a term usually applied to athletes or racehorses. I’d put on weight, and to her, being thin was yet another type of feminine power.

Her visit ended a few days later. I was angry she didn’t take me with her or even mention when I might see her again.

My hormones raging, I found that male attention could buoy a melancholy existence, at least for a little while. At 14, I crushed on a dark-haired boy who lived down the street and rode the bus with me in the mornings. I fantasized about kissing him. Older men, however, held considerably more sway over me. Certain types of men are attuned to unparented girls, ones who won’t make a fuss, who have already been conditioned to feel small. It was like ringing a dinner gong for predators.

Accepting a ride home from a much older instructor at the Y led to losing my virginity before my 15th birthday without so much as a kiss. When he said, “I need to stop at my house to pick something up,” and then, “Come inside,” I did. I didn’t know then what would happen next. I felt dirty and ashamed as I wiped the blood trickling down my leg. Afterward, he dropped me off at my aunt’s, and I attempted to glue myself back together emotionally. I told my cousin how upset I was over what had happened and that it felt wrong, but I couldn’t articulate much more than that. I danced around what happened in letters to my mother, hinting that I was having a hard time. The experience was hard to process and left me feeling worthless and overwhelmingly sad. If this was how men made you feel — disposable — I wondered what my mother saw in them. As far as I know, nothing happened to the asshole predator, and I suspect I wasn’t his only victim.

Things brightened when my mother’s new boyfriend brought me, then 16, and my brother to New York to live as a family, and they married. He was kind and offered a glimpse of what a real home was like with all the seats at the table filled. They also had a baby together, another boy.

“I think you’ll get married young,” she often told me in my late teens. “You’ll want to create some stability and start a family of your own.”

With her “seasoned eye,” she pointed out men she liked for me: a handsome traveler we met on vacation, a tennis player, and later on, a neighbor. “You need a spotter,” she told me. “I’ve been doing this longer. Sometimes you miss them.”

So like a cat bringing home a chewed-up rat for its owner, I claimed them as a trophy for her. I wasn’t interested in dating those men; I was trying to impress her with my own hunting prowess. See, I can do this, too. Like a skill transmitted through my genes, I rose to the thrill of the chase. Male attention made me feel alive — or at least seen. It was an effective means of escape, of forgetting myself. I gravitated toward addicts and cheaters; their attention lived elsewhere, and that felt normal. I dated a sensitive songwriter who was still pining for his ex, an actor who would disappear on benders for days, and a producer who forgot to tell me he had a wife back home.

At 35, I’d become a divorced single mom with my own baby girl. I didn’t want to repeat the pattern — my daughter deserved better. If there was such a thing as sex and relationship DNA, I needed to figure out how to shake it off.

This meant I had to reframe how I saw men and stop viewing them as “transitionary objects,” as one friend put it. That was all I had seen as a child, but I knew other types of relationships existed; other people had them. A therapist said, “When you get that feeling of great excitement about a man, register that as a negative.” So I let my hunting and fishing genes recede into the background and gave up on dating. Eventually, a friend set me up with a wonderful divorced dad. He’s the poster guy for loyalty and commitment. We’ve been together for 16 years and married for 10. My daughter has a doting stepdad, someone who shows up for both of us. She adores him, and he even brokers our disagreements.

It was a lot easier to criticize motherhood before I had my own kid. Parenthood comes with a certain amount of guilt and tests you in ways I never predicted. The perfect mother is a myth, but I couldn’t imagine leaving my child and missing such huge swaths of development. There are fragments of my memory that I still can’t access, that appear to me only in flashes and puzzle pieces I can’t comprehend. But I’ve stopped short of asking my mom, “Hey, what was that shitshow you dragged me through?” She shuts down questions about my childhood with “That was a very difficult time for me.” Or she says, “I don’t remember.” So we mostly leave those conversations alone.

What she doesn’t realize is it was a hard time for my brother and me too. We were along for the ride. My brother texted recently that she’d apologized to him for not being the mother she’d hoped to be. That admission felt shocking. Had she been the mother she’d wanted to be with me?

It took heavy lifting in therapy to develop some self-worth, but I’ve made progress and have learned to accept my mother for who she is. While she has been a devoted grandmother and propped me up through my divorce, I can’t totally erase all that has transpired. She remains mystified when she brushes up against the anger that still lingers in me and can’t grasp why I stopped longing to spend time with her. When the choice is between her wants and mine, I prioritize my own mental health over pleasing her. My survival demands it. She’s remarried and has moved away, but we speak frequently. The sex book appears to be on the back burner for the moment.

My daughter is 20 now and going on her own dates. Any hard-earned advice I could offer is useless in a Hinge world, so I sent her some self-help classics to fill in the gaps.

“Those old dating books aren’t relevant, Mom. Most guys my age aren’t looking for relationships,” she tells me.

“Your daughter has a very different life than you,” my therapist has reminded me in response to my fretting. It also helps that she has a sensible head on her shoulders and is far savvier than I ever was. Plus she has an extensive support network of family and people who love her. Our relationship is a close one; she knows she can come to me with anything. When she’s ready for a relationship, she’ll find one — and, as I know now, that usually happens when you realize you’re fine without one.