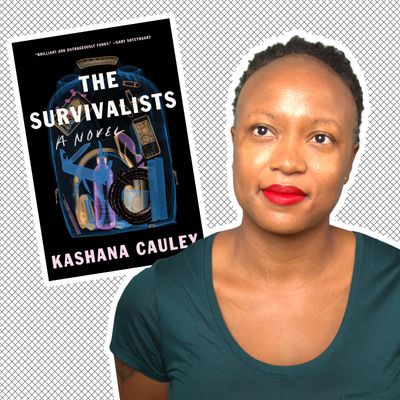

In good times, bad times, and times of exorbitant lettuce inflation, surviving in New York is an increasingly impossible feat. Kashana Cauley knows the struggle well. The TV writer, former antitrust lawyer, and now debut novelist — her book The Survivalists is out from Soft Skull Press on January 10 — lives in Los Angeles, but she remembers well the New Yorker’s ability to tolerate pretty much any structural inconvenience in exchange for a decent apartment. “My apartment in Prospect Heights was lovely, and the ceiling fell in three times, but it was below market rate and we held onto it for dear life, knowing we’d one day be priced out and that was going to be it,” Cauley says. “I loved it there. I loved the neighborhood. My kids loved everything. I really wanted to survive there. But it was so hard.”

Set after Hurricane Sandy, The Survivalists follows Aretha, a single, straitlaced Black lawyer trying to make partner at her corporate law firm while also trying to stay afloat in the city. Originally from the Midwest, Aretha loses both of her parents in an accident and her desire for home in both the metaphorical and physical, rent-paying sense leads her to fall in love with Aaron, a coffee entrepreneur and fellow orphaned millennial who owns a Brooklyn brownstone. Soon enough, Aretha moves in. The only catch? Aaron’s roommates (and maybe Aaron himself) are doomsday preppers who stockpile guns and build bunkers. Aretha is initially skeptical of the survivalist lifestyle and the illegal guns, but once she falls off the corporate ladder, she slowly becomes enmeshed in the roommates and their logic. Disaster could strike, and who would protect them if it did? It’s not long before Aretha is skipping brunch with best friend Nia to live on soy bars and go on gun runs herself. Call it extreme, but underneath the apocalyptic antics, Cauley’s question is a reasonable one: What would you do for a free home in New York?

Aaron is a coffee entrepreneur, and I must preface this interview with a very important question. How do you take your coffee?

Black, just like all the sociopaths. Right now I order from a local coffee shop called Go Get ’Em Tiger. They have a “coffee of the month” club where they send cute postcards and tell you what notes are in your coffee, where the farmer’s growing it and under what conditions. I’ve ordered from Texas and Brooklyn; I’ve gone all over the world to sample coffee. I’m obsessive, and I’m sure that comes through in the book. Shout-out to the Salvadorans, who were the only good roasters in Paris when I went.

The book looks at survivalism through a lens of dark humor. Aaron’s roommates are doomsday-prepping in these over-the-top ways, but Aretha’s arc also speaks to the difficulties of just living in the city while trying not to fall off the corporate ladder. What was your inspiration for the novel?

I lived in Brooklyn for six years, and while I was there there were two articles about people stockpiling guns in New York City. One of them was at the end of my block in Prospect Heights, above an upscale ramen shop. I was just like, Guys, we have no crime. In the middle of rapidly gentrifying Brooklyn, why are you so afraid someone is going to come and get you? Around that time there was also news about a white couple stockpiling guns in the Village. I was easily perplexed, like, Guys, this is the Village! The scariest thing that’s going to happen to you is the prices they’re charging for food in those cafés.

But I also came from a household where my parents owned a handful of guns. They’re just-in-case people. I don’t know whether they’d describe themselves as survivalists, but I don’t think that most survivalists necessarily do. They had real fears, even if the contours of those fears were a little nebulous and undefined. All that and the fact that surviving in New York City is impossible inspired the book, I would say.

You’ve written op-eds, for television, The Daily Show, and more. What was it like approaching a novel?

I have three dead books that will never be published, so I had a process and a practice. I started The Survivalists in late 2017. I had an outline and a three-act structure I learned from TV, which I know sounds basic, but there’s a reason a lot of stories are structured that way and you can arrange a lot of poignancy around them. At the time, I was also working on a sitcom, which are very formulaic, and I structured this book like a sitcom.

Like Aretha, you were a lawyer. Did you draw any inspiration from your own career path when you were writing her story?

I was an antitrust lawyer for five years. I probably became a lawyer for the wrong reasons. It had a lot to do with being a first-generation college student and not knowing what people were supposed to do with a degree. I took the LSAT on a whim and ended up at a white-shoe law firm, which is an extremely weird place to be when you’ve been raised working-class. I felt self-conscious a lot. I was the person who wore suits more often than anyone else; I had something I was trying to prove. High-end law firms are also very white, and I’m a Black girl. They’re competitive. I also came into law at a time when there was less of a future in it than the lawyers practicing before me. We weren’t making partner, and in 2008, partners were being canned as much as associates.

Law school teaches you to be competitive and firms enhance that, but the majority of us were losing, and that perspective influenced a lot of the legal stuff in the book: that feeling that you’re doing all of this work that isn’t necessarily making you happy because you’re not representing people who do nice things. The companies are doing work that doesn’t benefit people, and the lifestyle is brutal. I sometimes joke that I could have gone to concerts and had friends during the time I practiced instead of falling asleep on the couch at 4 a.m. writing briefs.

Aretha has lost her family, and her Achilles’ heel seems to be her desire for a home, even if that means a home with a bunker with Aaron’s gun-running roommates.

Some of Aretha’s home longing comes from the loss of her parents and the desire to stay in New York. For me and all my New York friends, it was always sort of like, When is the next rent increase going to come and price us out of here and make us leave our friends and communities behind? We’d always talk about whether there was any way to make enough money to own a place so we could solidify our circumstances and stay. That’s always on the back of Aretha’s mind as a potential spoil of success. But how Brittany and Aaron and James own a house is amazing to Aretha. Everyone’s an old millennial, and millennials don’t own brownstones in Brooklyn. They don’t have that kind of money. And she’s sort of amazed how they’ve achieved it, even though they’re weird and violent and stockpile guns.

Aretha first approaches the doomsday-prepping with skepticism, but over the course of the novel she really becomes part of that lifestyle, subscribing to it even when Aaron is away on coffee runs. She gets a chance to quit her old life. How did you turn such a straitlaced character into a gun runner?

Oh, it was so fun. I’m a straitlaced, boring person. Aretha is not me, but it was fun crafting a character who is also straitlaced and fully lets go of it because she knew she wasn’t going to make partner, so why not do something more entertaining with her life? On top of all that, Brittany and James and Aaron own a brownstone and run a business. They have control of their lives and on some level Aretha is like, Is this how they did it? I don’t understand gun running and I don’t necessarily like it, but is it part of the secret sauce? So she keeps wanting to get closer to it, and it’s thrilling. She’s spent a lot of her life sitting in an office and following rules. All of a sudden, she gets to do something. Even if it’s not the world’s best idea and is in fact, illegal, it’s exciting to do something different. She feels free. She feels like she’s becoming someone else, and that new person is much more exciting than her previous self.

Yeah, and she even starts eating the soy Life Preserver bars.

The soy bars are nasty. Yet as the book goes on, she’s like, These are delicious. It’s real Stockholm syndrome.

I really loved Aretha’s friendship with Nia, who’s there for her without question even as she gets sucked into a cult and without hesitation once she’s out of it.

I had a very long-term friend, and we went through it all together. She got into some bad relationships and bad hookups and we ended up accidentally living in a house full of drug dealers. There was this dead guy who showed up on our couch. Nobody knows how he died! It was like, There’s a dead guy on your couch and the cops may want to talk to you. She and I went through a lot of crap together. But at various points, when we were given the opportunity to not be friends, we made the decision to keep the friendship going. It was an intimate friendship, and though some of it was longevity, it was also our sheer desire to remain close. We’re not actually in touch anymore. But that gave me 15 years of, What if friends decided that no matter what, the friendship was above all?