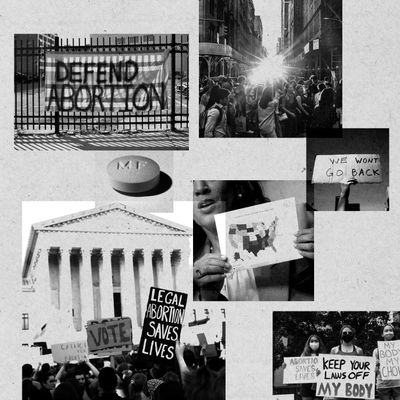

A bill that would prosecute abortion seekers for felony murder. New bans on abortion starting at fertilization. Measures to amend state constitutions to exclude abortion from the right to privacy. These are just some of the bills Republican lawmakers have introduced in the two weeks since state legislatures reconvened for the first time following the overturning of Roe v. Wade last summer. Add to this mix ongoing legal challenges and a new, divided Congress, and so many new fronts are appearing in the battle over abortion rights that it’s tough to keep track of them all. “Abortion opponents are gonna use every legal mechanism at their disposal to limit care — whether it’s in the legislature, in the courts, or through regulation,” says Elizabeth Nash, who leads the state-issues team at the Guttmacher Institute.

The Cut asked more than 20 abortion-rights advocates and experts, including abortion providers, abortion-fund staffers, researchers, and lawyers, what they expect to see in 2023. Everyone agreed the dust has far from settled after Dobbs, with the abortion-rights landscape likely to get much worse before it gets better.

New ways to make life hell for abortion seekers

While abortion is currently banned in 14 states, some patients have found ways to obtain care anyway, and conservative lawmakers are racing to introduce measures to close those gaps. “They’ll be using indirect methods to limit people’s options,” Nash says. In Texas alone, lawmakers are floating bills that would allow a state attorney general to step in and charge people with violating the law if a local prosecutor declines to do so; introduce a tax penalty on companies if they have policies in place supporting employees seeking an abortion; and block websites that share information on abortion care.

A dozen or so states that already heavily restrict abortion but do not fully prohibit it — such as Florida, Iowa, and Nebraska — could go as far as banning abortion at around six weeks, before most people even know they’re pregnant, without exceptions. In Wyoming, lawmakers are considering banning the procedure starting at fertilization and making performing an abortion a felony. Other states are attempting to subvert their voters’ will: In Kansas, conservative lawmakers are pushing a fresh slate of abortion restrictions, even though in August people voted in record numbers to keep the right to an abortion in the state constitution. It’s clear that anti-abortion lawmakers will “be turning themselves into pretzels to use the law to prevent people from accessing care,” Nash says.

Blue states stepping up in bigger ways

States across the Northeast and the West Coast plus Illinois and Minnesota are expected to introduce more proactive abortion legislation. That can look like enacting shield laws to protect providers who mail abortion pills to patients in banned states, requiring health-insurance plans to cover abortion care, or codifying abortion rights in state law.

Morgan Hopkins, president of the abortion-rights coalition All* Above All, also anticipates efforts to expand and protect access to abortion care at the local level. She points out that, shortly after the fall of Roe, cities like Atlanta, Austin, and St. Louis — all in states that have banned abortion — allocated funding to help abortion seekers cover the cost of travel, child care, and other practical needs. Lawmakers who support abortion rights have an opportunity this year to be bold and work to remove the barriers to access that persist even in the friendliest of states, Hopkins says. “We need to be thinking bigger than just restoring the protections of Roe v. Wade,” she adds.

A showdown over abortion pills

Even before Roe was overturned, medication abortion had been the most common method of terminating a pregnancy in the U.S. Patients have continued to access medication and self-manage their abortions in states that have outlawed the procedure. The Biden administration also finalized an FDA rule change this month that will allow pharmacies to dispense mifepristone, one of two pills used for a medication abortion, in a move that could widely expand access to care. Advocates say they’d like to see the administration go further and do away with other regulations they consider unnecessary, such as requiring that clinicians prescribe abortion pills and that pharmacies become certified to dispense mifepristone. These regulations do not apply to other medications.

Access to abortion pills has presented a major obstacle for abortion opponents, who are desperate to crack down on the medication. While lawmakers think of ways to restrict the distribution and use of abortion pills, opponents have taken to the courts to try to blunt their impact. In November, anti-abortion activists filed a lawsuit attempting to reverse the FDA’s decades-long approval of mifepristone. The case is currently being heard by a Trump-appointed federal judge with a track record of railing against LGBTQ+ issues, birth control, and abortion. “In a nutshell, this case is an attempt to have a nationwide ban on medication abortion,” says Jenny Ma, senior counsel at the Center for Reproductive Rights. “This is not just another lawsuit in a long string of abortion lawsuits. This lawsuit may have nationwide effects and may have an effect that is greater than when the Supreme Court overturned Roe.” The case could be decided as soon as February 10.

Demonizing abortion funds

Abortion seekers’ financial needs have skyrocketed post-Roe as people are forced to navigate increasingly complicated logistical challenges, including traveling greater distances to obtain an abortion and facing delays in care at overwhelmed clinics in permissive states. Abortion funds have remained a lifeline for patients during this time, though several organizers say the record-breaking uptick in donations and volunteer applications these grassroots groups received last summer has plateaued.

Legal complications may be on the horizon for these funds as lawmakers in hostile states begin exploring legislation that could directly target them with “aiding and abetting” measures or requirements on how these organizations can use their funding. House Bill 61 in Texas, for example, would prevent governmental entities, such as the city of Austin, from directing money to organizations that offer logistical support — including travel, lodging, child care, and food — to abortion seekers.

Attacks on information about abortion

Legislators across the country are weighing measures that would block abortion-related websites, ranging from resources that allow abortion seekers to order medication online, such as Aid Access, to those that offer information on how to do so, such as Plan C and Mayday Health. As part of this effort, abortion opponents have floated the idea of using the Comstock Act — an 1873 law that banned the mailing of contraceptives and other “obscene” materials — to prohibit so much as speaking about abortion.

Abortion-rights advocates say such bills would likely face legal challenges if signed into law. “We’re confident that we are protected under the First Amendment, and the baseless threats won’t do anything to stop us,” says Rebecca, founder of the site I Need an A, which helps people find information about abortion clinics, support organizations, and other resources. (Rebecca asked that her last name be withheld to protect her privacy.)

But lawmakers are not the only ones who can curb patients’ access to information. “Unfortunately, censorship is already happening in other ways,” Rebecca says. “Places like Whole Foods block access to our website, and we suspect there are schools and universities doing the same.” I Need An A suggests the use of VPNs to circumvent these restrictions anonymously.

Post-Dobbs births and their outcomes

The end of March will mark nine months since the Supreme Court decision, which means a first wave of patients who were denied abortion care will be forced to give birth. Dr. Diana Greene Foster, an abortion researcher and author of The Turnaway Study, says researchers estimate that one-quarter of people who would have been able to get an abortion in their state prior to Dobbs will not be able to — likely resulting in between 50,000 to 75,000 additional births each year.

Foster cautioned that this won’t translate into an indefinite increase in the nation’s fertility rate, however. “When people are unable to access an abortion, they are less likely to have wanted pregnancies later under better circumstances,” she says. “The net effect of not being able to get an abortion is that people will have babies at a time when they don’t have the financial resources, social support, strong relationships, life circumstances — and then be less likely to have wanted pregnancies later, either because they have all the children they can care for or because the better circumstances are less likely to emerge following the strain of raising a child that they were not prepared for.”

Abortion-rights advocates are also concerned about the outcomes of these births. Maternal mortality remains a huge issue in states that have banned abortion post-Dobbs: Women in these states are nearly three times more likely to die during pregnancy or childbirth or soon after giving birth, according to a Gender Equity Policy Institute report. There’s also a connection between being denied an abortion and worse birth outcomes, Foster says. Research has found that patients who were forced to carry a pregnancy to term report more life-threatening complications such as eclampsia and postpartum hemorrhage.

Sneaky ways to punish abortion seekers

Only two states currently ban self-managed abortion: Nevada and South Carolina. The majority of bans target people who perform abortions, due to the fact that prosecuting abortion seekers themselves remains a deeply unpopular position — only 14 percent of Americans believe women should serve jail time if they have an illegal abortion. And yet lawmakers in Oklahoma and Arkansas this year introduced legislation to punish people who terminate their pregnancies.

It’s unclear if such measures will gain steam, but Jill Adams, executive director of If/When/How, a reproductive-justice legal nonprofit, expects abortion opponents to use other laws already on the books to prosecute abortion seekers. Even while Roe stood, between 2000 and 2020 at least 61 people were investigated or arrested for allegedly self-managing their abortions. Alabama attorney general Steve Marshall recently pushed this idea, arguing that women who use abortion pills could be charged under the state’s child-endangerment laws. (He walked back his comments after public outcry.)

“Abortion bans and restrictions, while they don’t directly authorize states to criminalize people who have abortions, do foment abortion stigma and antipathy towards people who have abortions,” Adams says. “You combine that with an emboldened police state, and that’s likely to generate more unjust arrests, investigations, and prosecutions.”

She also points out that marginalized communities — people of color, immigrants with vulnerable status, transgender and gender-nonconforming people, and folks struggling with financial insecurity — are more likely to be punished for having abortions. They also understand best how to move forward. “The loss of Roe is significant, undeniably so, and 2023 will be different than any year in the previous 50 for everyone in the abortion ecosystem,” Adams says. “And yet there are many people for whom Roe was never enough. If we are wise, we will listen to them.”