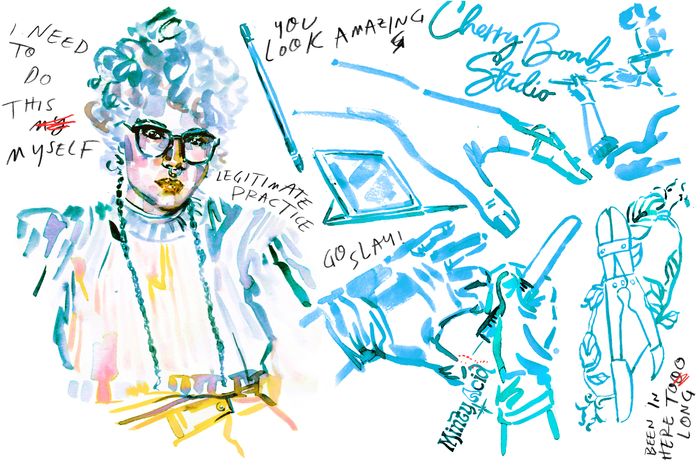

Workplaces, especially offices, are often called “sterile.” Cherry Bomb Studio, where Ifé Toussaint works, actually is sterile, but it certainly doesn’t feel that way. The Eldridge Street space feels like a hair salon crossed with a friendly dungeon thanks to the black latex that lines all the chairs and equipment tables. Multicolor chandeliers hang from the low ceiling, and large mirrors are graffitied with affirmations like “Go slay!” and “You look amazing.” Nineties rock by women plays at the perfect volume, audible but nonintrusive. The crew of piercers and tattoo artists, all femme or nonbinary, are perpetually busy: sterilizing equipment; welcoming customers; and decorating septums and brows with jewelry, teeth with gems, and limbs with ink. Yet they also find time to joke around, share snacks, and admire one another’s work with genuine sincerity and sweetness.

Toussaint, who’s 24, feels incredibly lucky to be working at a studio like Cherry Bomb; a lot of tattoo studios, we agree, have a macho vibe. Toussaint started there only recently, after launching a business tattooing from home, then doing a guest spot at a studio in their native Puerto Rico. They exclusively do stick-and-poke tattooing, which requires a slightly greater degree of control and dexterity than tattoos done with a gun.

The lines of a hand-poked tattoo are sometimes a little wavy or shaky, a snapshot of a human touch in a specific moment. Toussaint’s designs tend to have a fanciful, filigreed effect. Their flash includes imps and fairies, swords, and sparkling stars. The swirly shapes let them showcase their ability to create preternaturally smooth lines and curves. Toussaint is also a radiant, soothing presence — an important quality in someone who’s about to spend a few hours jabbing your flesh repeatedly with a needle. I was curious to know how a tattoo artist makes it work financially, especially one who’s just starting out.

Toussaint and I met in the psych ward. They were experiencing a depressive episode; I was manic. I got incredibly lucky: We were roommates. The days felt endless and we weren’t allowed outside, but talking to Toussaint made the time seem to pass more quickly. During “quiet hours,” when we weren’t allowed to leave our room, we would sit on their bed and watch the clouds roll across the sliver of sky and the East River that we could see from the corner of our window. When we were allowed out, we gravitated toward the common room, where we read each other’s tarot cards and played board games with our ward mates. We made beaded bracelets in art therapy, made fun of the music-therapy teacher’s love of Alicia Keys, ate our sad mashed-potato-centric meals at our adjoining desks, and listened to music together on Toussaint’s phone (I didn’t get phone privileges). One night, Toussaint showed me photos of the tattoos they had done. I was ready to get tattooed by them then and there, and if there hadn’t been a total lack of sharp objects around, I would have. But we did settle on a design: bolt cutters, to commemorate our mutual love of Fiona Apple, not to mention the compelling sentiment that we had “been in here too long.”

Months later, we reconvened to make this dream a reality. While we talked, Ifé drew on a tablet with a stylus using ProCreate, filling in the details of the design they would later tattoo on my arm.

Toussaint did their first tattoo on themself, at 15 or 16, at an art camp in Florida. Another camper had managed to use needles, a lighter, and India ink to give themself a tattoo of a little alien head. “I was like, I need to get in on this,” Toussaint recalls. At first they were going to let a friend tattoo them but then changed their mind. “I was like, ‘No, I need to do this myself.’” The tattoo, the glyph for “female,” is on their inner ankle. Since they now identify as nonbinary, they find this particularly cute.

They attempted some other career paths before settling on tattooing, including freelance illustration and graphic design, which they studied at SVA before dropping out. “It’s just such a cutthroat industry, and it was just really competitive at SVA, and it was making me more depressed,” they say. “And it wasn’t fulfilling me. I feel like my vocation is to do things that make other people feel happy and better about themselves.”

Toussaint uses Instagram to promote their tattooing, making Reels and posts about new flash, availability, and recent work. Their network isn’t huge — 469 followers — but it grows each time a new client gets tattooed; word of mouth from happy customers has enabled Toussaint to grow their client base slowly but steadily.

In a shop like Cherry Bomb, artists pay the studio a percentage of their earnings on each piece, about 30 percent. The fee goes toward the space and all the supplies except inks and needles, which artists provide themselves. “Ink and needles are a very personal choice depending on the kind of art that you make,” Toussaint says. “All my needles are specifically tight, round liners, for making perfect lines without it looking more spread out.”

Toussaint charges $100 an hour for a session, and customers are expected to tip at least 20 percent. Toussaint’s goal is to make three times their monthly rent — $1,087.50 — every month at the studio, with $2,000 as a floor. That works out to 20 to 30 hours spent in a tattoo session per month. That’s not impossible, but it’s certainly a strenuous amount of physical and creative work. There’s also a lot of unpredictability in the job: They rely on a combination of bookings and walk-ins and big and small pieces. They don’t have a lot of control over who wants what kinds of tattoos at any given time. “It’s sort of stressful to think about because there’s no set amount of money that I am going to make every week,” they explain. “As I build my clientele, I feel like it’ll come more smoothly.”

It hadn’t occurred to me until Toussaint mentioned it that tattooing has busy seasons and slow ones, for sort of funny reasons. Pre-Christmas is slow because no one wants to come home for the holidays with fresh ink. “But right after Christmas, because everyone got their Christmas money, people are getting tattoos and then it’s like, boom,” they say. “This month for me was pretty busy compared to how it was at the beginning of the winter.” The hottest months of the summer are also slow; you can’t really go swimming, sunbathe, or sweat with a new tattoo.

After about 45 minutes, Toussaint finishes their stencil, which they then print out on translucent temporary-tattoo paper and position on my arm. I’m curious about what I should expect from a stick-and-poke this big. Will it hurt more or less than a machine tattoo? “That depends on the person,” they demur. “But it’s less impactful to the skin, so it’ll heal a lot faster.” I get into position and let them do their thing without pestering them with questions. It definitely hurts less than a machine tattoo — so much less that I begin to find it kind of soothing. Some tattoo artists like to chat like hairstylists, but Toussaint likes to focus on their work. I let them.