This article originally appeared in Brooding, a newsletter delivering deep thoughts on modern family life. Sign up here.

There are not enough spaces in my life that are status neutral. Everything from the sheen of my wall paint to the thread count of my bedspread says something about me and my values and what I can and can’t afford, and it’s exhausting as well as boring. Even my fridge is in the mix now; many bougie fridges don’t have magnetized fronts anymore because people prefer a more minimalist look, and really bougie fridges don’t even look like fridges — they’re paneled to look like built-in cabinets.

When we bought a new fridge a few years ago, we chose a white one because we wanted to put stuff all over it. I didn’t realize until recently that this practice has been enfolded into the overall nostalgia for the ’90s. The other day, I was listening to How Long Gone, and the hosts were warmly reminiscing about “’90s fridges” that were a 20th-century mother’s chaotic and intimate curatorial space. Magnetized fridge fronts are now a sign that either your fridge is old or you’ve made a folksy decision to forgo the clean pillar of stainless steel or the false-modest ostentation of the fridge hiding in plain sight.

Family-photo curation has now migrated from the kitchen mishmash to the “gallery wall” — a trend that, to my mind, reflects the growing influence of the visual logic of social media on the inside of our homes (as well as on our bodies).

Our relationship to photography has changed a lot over the past 20 years. When we pose for a shot, we know it will very likely be served to a virtual public, and we arrange our bodies and faces accordingly. We’re self-conscious about being on display. Likewise, we’re self-conscious about displaying our pictures — we like them to look deliberate, not haphazard. Hence the gallery wall.

Kitchens, meanwhile, have become important canvases for the aesthetics of status, full of big, clean, minimalist surfaces. All of this has been hastened by Instagram. My friend Sophie Donelson, a design consultant and author of the forthcoming book Uncommon Kitchens, reflected on the move from fridge gallery to gallery wall. “As the kitchen has become a greater and greater showpiece, the threshold for evidence of chaotic living has gone down,” she said. (Some people have “back kitchens” now, separating chaotic living from public-facing living.) “The kitchen was the center of life, and it had the accumulated evidence of life. And the fridge was the de facto place to display it.”

Donelson understands the appeal of the gallery wall. “Sending your photos to be printed out, matted, framed, and sent back to you, all from your phone — it works really well for busy parents,” she said. But the convenience can come at an expense. “When you make something uniform, people stop seeing it. You see this a lot in decoration, what some people call the Airbnb-ification of interiors.”

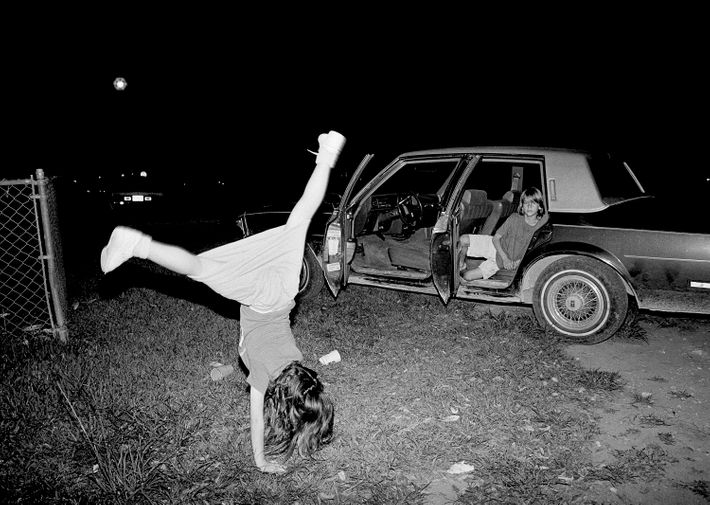

Two recent books have been reminding me of how much social media has changed our approach to family-picture-taking and posing: Black Archives, a riveting collection of snapshots of Black people in public and private over the past 50 years collected by Renata Cherlise, and Juggling Is Easy, photos that the artist Peggy Levison Nolan took of her seven children while she was raising them alone in South Florida in the ’80s and ’90s.

Many of the photos in Black Archives have the formal quality of a gallery wall — pictures of milestones, trips, family gatherings. But you feel a sense of intimacy and trust in the pictures that is rare to see in today’s digital images snapped for sharing. And the ephemeral quality of film photography is incomparable.

By contrast, Juggling Is Easy’s images are candid and very rarely posed, the result of years of Nolan documenting her kids to the point that they were no longer aware of the camera. But Nolan’s work bears no resemblance to the equivalent omnipresent documentation by today’s momfluencers.

I called Nolan on her landline recently to talk about family photography past and present. “We are much more self-conscious, because of social media, than we have been in any other era,” said Nolan. “The family photograph is a very good indication of how folks want to be seen now. I think that everybody is aware of how things look in a formal way now. This is my house. This is my new manicure. This is us in front of the Grand Canyon looking like idiots.”

Nolan wondered if displaying photos on a gallery wall reflects some of the pressure that social media has created — even among those of us who don’t use it much — to “look better than you are,” as she put it. “It’s always about looking better than you are.”

The gallery wall honors that self-consciousness with a formal display of everything a family stands for. We’ve gotten the hang of posing for pictures as if we were public figures or influencers, and the gallery wall provides a place where all that effort can be recognized. The gallery wall is a domestic-branding exercise. The fridge gallery never worked the same way; it mixed snapshots with calendars, reminders, permission slips, and mementos.

I don’t have a problem with gallery walls, but let’s admit that they’re giving “In Memoriam.” The joy and triumph frozen in time — is it a living, breathing thing? We had a gallery wall in our old apartment, but when we moved a few years ago, there wasn’t quite the right wall for one in the new place, so all the framed family shots live in a box in the closet. The gallery fridge is sacrosanct, though; I will never live without one. If the gallery wall is designed to show us as we wish we always were, the fridge is where the flotsam of our actual lives is on display.

The work in Juggling is Easy made me more than nostalgic — more like bereft. The piles of kids and the ambient chaos remind me of where I lived in high school, a big rambling house that my stepmother owned and kids called “the Manor.” The Manor’s doors didn’t lock, as I recall. Kids came and went, friends of mine and my step-siblings’, kids living there long term if there was trouble at home, kids in the papasan chair slurping instant ramen, on the back porch smoking. The Manor’s central location in town, combined with the parents’ light supervisory touch, made it a critical meeting place throughout high school. I was lucky to have lived there.

Another décor trend invited into our homes by social media are the signs with words that evoke feelings of well-being: “gather,” “Sit long, talk much.” There’s an unintended poignancy to displaying how-to instructions for things we are supposed to have instincts for. Donelson wonders if the denuded décor of the Instagram age has left us in need of instructions for how to behave in our own homes. “If you paint your cabinets purple, you don’t need to be reminded to ‘live, laugh, love,’” she said. Hang all the “gather” signs you want, but if your house isn’t chill and inviting, no one is coming over. Likewise, the gallery wall conveys what a family wants you to know about them — but those of us who really know them? Our knowledge is fridge-door level.

A gallery wall is a mood board for love, aspiration, belonging, and, yes, status. This is the place where we demonstrate how our families make the most of the seasons. Here we are at the beach, and here we are in the snow! Here we are among the elderly, and here with the very young! See how we taste the fruit of life — see how we suck out the juice? All of this is wonderful, and those of us who get to create these walls are fortunate. But something is missing.

I asked Nolan why she thinks her work is resonating right now amid the filters and TikTok challenges that define our way of representing ourselves. “The age that my kids were when I took those pictures, what really mattered to them was community. That’s what they cared about. To deprive them of that would have been awful — I would have paid the price.”

More From This Newsletter

- Parenting Through Our Control Issues

- When Kids Are Addicted to their Phones, Who Is to Blame?

- Why Are Parents On TikTok So Angry?