Swellness is a monthlong series exploring the health and wellness stuff no one talks about.

When I first began working in the clean-beauty and wellness space, I didn’t know what I was stepping into — or, rather, onto: The store was built on a bed of rose quartz, I learned in my second interview, for its medicinal properties of self-love. That was the first sign this was no ordinary retail job. I wasn’t going to be selling the many beautiful vials that lined our shelves but the intoxicating promise of becoming your best self. This was almost six years ago, before the words clean beauty or wellness were ubiquitous and interchangeable.

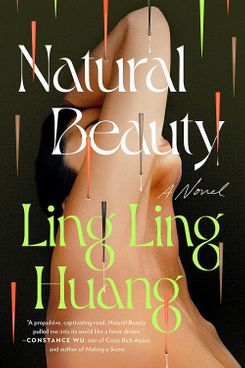

Working in this space raised a lot of questions for me. Attempts to answer them turned into my debut novel, Natural Beauty. My book has been called many things, including speculative fiction, literary fiction, and body horror. But, for me, it is sheer fantasy — the fantasy of escaping the performance of gender and the constant appearance labor our hypercapitalist society expects us to maintain.

The book’s title stems from a fascination with the term. Together, the phrase natural beauty acknowledges that those at the top will always be those who were born there, people for whom everything comes naturally. It also catalyzes the desire and subsequent consumption of products for those of us who want to appear more fortunate. Natural beauty and its subsequent iterations (clean-girl makeup and no-makeup makeup) imply that there’s something frivolous about chasing beauty even though it’s one of the only ways women have historically been able to obtain social and economic power. Now science-backed skin care and makeup repackages appearance labor as an intellectual exercise. There’s something misogynistic and judgmental about this concealment, the sense that we should never look like we’re working too hard (how embarrassing!) on our exterior.

Natural Beauty questions the rate at which we have bought into the idea of self-care as a construct that actually serves us. Working in the wellness industry did not make me well, nor did it make anyone else who was working there well. People tried new diets and unregulated ingestibles like fast-fashion clothing items. I saw how quickly environmental concerns regarding the purity of food sourcing could become orthorexia, which one could say is a greenwashed iteration of anorexia. So many product ingredient lists read like topical salads, containing food items that my co-workers and customers gladly put on their faces but would never put inside their bodies. One girl I knew claimed she could consume only medium-rare beef and minced carrots and eat just three days a week. I quickly realized that I would have to mentally protect myself from an eating-disorder relapse and that a lot of “wellness” (the goops and glugs and tonics and teas) was a way to circumvent caloric intake.

It became clear that the objective of wellness was beauty. In fact, it didn’t seem possible to be well without also, and maybe first, being beautiful. The two terms are enmeshed by design. I lived in windowless rooms slightly bigger than coffins and crashed on my brother’s couch during the time I was selling $500 face creams to actresses. I was commuting up to four hours a day, making just enough money to eat, and when I fell down a flight of stairs, I hobbled around on a sprained ankle for weeks because I didn’t have health insurance. But, of course, I spent the little money I made at the store where I worked on wellness and clean-beauty products that promised to change my life. I was an American doenjang girl. And can you blame me? Beauty is deeply tied to economic success. Why else would Zoom, a videoconferencing technology used for meetings, have the option of “touching up my appearance”? Technology shows me how I’m supposed to look while ensuring that I can get to work faster, presumably so that I can make more money to buy the products or procedures I need in order to look more like my poreless online avatar.

In a bizarre twist, I’d never seen my culture more represented than when I worked in the clean-beauty and wellness industry. Where natural beauty is focused on extracting the best of the natural world, wellness often takes from other cultures. The exact same Chinese traditional-medicine products I could get in Chinatown were sold at a much higher price at the store where I worked. Same with Ayurvedic products and ancient Japanese items used by geishas. The difference was high-end packaging and their availability in a location completely divorced from connecting with the culture itself. Not having to go to Chinatown was perhaps worth the much higher price. In this, I saw the ghost of the gig economy, which prioritizes extraction of work from people sans interaction. More troubling was the fact that there were many cultures absent from our shelves — ones that weren’t deemed worthy of commodification for my mostly white and extremely wealthy customers. The line between representation and fetishization is remarkably thin.

I have begun to think of beauty as Janus, the two-faced god who can see into the past with one face and into the future with the other. The power women can yield from beauty speaks to a forward trajectory of our liberation, but that self-expression is so often coopted in ways that move us back under patriarchal, classist, and racist systems. My ancestors in China established foot-binding as a status symbol, and today in South Korea, women get their calf muscles surgically removed in order to have thinner legs. We’ve internalized our oppression and the idea that women have always been most beautiful when they are least mobile or functional. The beauty and wellness industries are like those magnifying mirrors, turning everything about me into a problem with a viable (and expensive) solution. The harder I tried, the uglier I felt. As feminist philosopher Sandra Lee Bartky once said, “The disciplinary project of femininity is a ‘setup’: It requires such radical and extensive measures of bodily transformation that virtually every woman who gives herself to it is destined to some degree to fail.”

And fail I did. Not only did I still have pores, but my bank account and mental health were in total disarray. How could my life be falling apart when I was using all the right products and taking a dangerous amount of supplements? I learned the hard way that you can consider appearance labor only when your basic needs are met, and in this way, capitalism has created a scarcity that’s a distraction. Appearance labor is often a form of survival for women, but it is also the very thing that chains our worth to how we look. Another job opportunity arose, and I was thankful for a reason to quit, disillusioned and disoriented.

I spent the next few years trying to put that experience into words. I had been conditioned, literally groomed, to think that a new face mask or the right adaptogenic tonic could solve all my problems. These industries are so loud, and their messaging so subtly crafted, that I had stopped being able to hear what my actual needs were and had become completely disconnected from my body. I couldn’t begin to care for myself because I didn’t know who that self was.

Writing the main character of my novel widened my tunnel vision, the first of many steps I would eventually take to “unself,” a concept writer and thinker Iris Murdoch used “to pierce the veil of selfish consciousness and join the world as it really is.”

The beauty and wellness industries had coopted my attention and taken me away from “the world as it really is.” I had become my own magnifying mirror, incapable of seeing anything beyond my own reflection. Any counterpoint to the ideas these industries manufactured were out of frame.

In the years since I worked in the industry, I’ve had to create wellness on my own terms. I’ve had to rediscover my actual needs, most of which are unrelated to my exterior. My favorite ways of practicing “unself-care” are spending time in nature, writing, and playing violin. Unlike screens and storefronts, trees aren’t selling me anything or trying to change me. For as extractive as the beauty and wellness industries are, they mostly extract from us, the consumers.

From nature, I am learning how appearance is tied to functions of survival, how intelligent and self-supporting our bodies already are. I am learning how to coexist and how to be in community with others. And, most of all, I’m falling in love again with wildness. The longer I spend in brambles and liana and see the proliferation of difference nature has to offer, the more I learn to prize uniqueness over homogeneity. The wilderness doesn’t mistake sameness for belonging. Writing and playing violin are creative acts for me, and every time I do them, I challenge the notion the world feeds me that I am only a creature of consumption. There is no “best self” with them, only constant improvement according to my own standards.

My interest in beauty started when I was a young girl. Now, so many decades later, I recognize that what I’ve always sought from beauty is a sense of acceptance and community. For a long time, I had mistaken sameness for belonging and thought that I just had to keep working, that the reason I was failing at beauty and belonging was because of me. But, in truth, wellness as it is sold and packaged by companies today only made me poor, depressed, and ill. I didn’t fail — the wellness and beauty industry failed me.

More From This Series

- Things We Tried and Would Use Again

- I Tried It: Estrogen Face Cream

- What to Do (and Not to Do) When Your Friend Has a Newborn