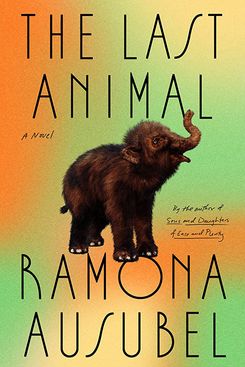

In 2015, a Harvard geneticist began a mission to “de-extinct” the 4,000-years-gone woolly mammoth by combining DNA from a frozen mammoth specimen and Asian-elephant genes. To many scientists, the project was overambitious, poorly conceived, and ethically questionable. To novelist Ramona Ausubel, it was ripe with creative possibility.

The idea for Ausubel’s new novel, The Last Animal, took root when she saw a segment about mammoth de-extinction on the news after giving birth to her first daughter. Her book places the quest to repopulate the earth with an ancient species in an entirely unexpected context: Instead of focusing on the grand scale of evolution and extinction, The Last Animal is an intimate story that follows Jane, a recently widowed mother, and her two teenage daughters, Vera and Eve, who attempt to resurrect the mammoth on their own terms. Even though their mission could change the planet as we know it, Ausubel tells their story with the humanity and warmth of a fairy tale, making it feel simultaneously more magical and concrete than a series of fancy experiments conducted in an Ivy League lab.

When the manuscript was first making the rounds, it landed in the hands of Jenny Slate. The actor fell so in love with Ausubel’s writing that she ended up writing a blurb for the novel’s cover. “I was so excited that this is the story someone is trying to tell me,” Slate recalled. It’s not a huge surprise that she was drawn to it — as a creator of Marcel, the titular shell with shoes on, she too has a knack for making strange, whimsical creatures feel both real and emotionally resonant. In a conversation mediated by the Cut, Slate and Ausubel talked about their shared approach to storytelling and finding magic in the minutiae of everyday life.

Ramona, where did the conceit for a woolly-mammoth–elephant hybrid come from?

Ramona Ausubel: When I started this book, my daughter, who’s 8 now, was a tiny baby, and a news feature flashed across my screen: People are going to re-create the woolly mammoth. At the time, my perspective on it was a little cynical: Why do we do these things? Why can’t we just take care of the dumb planet and one another and stop coming up with these harebrained, ridiculous concepts? But the more I wrote, I grew more tender to it. At least we’re aiming for a bigger, fuller world that’s got a big giant fuzzy elephant in it again. I like that world! Seeing that sweetness in the big brainy human impulse felt really encouraging to me.

Even though the story is set against the very bleak reality of climate change, it feels sweet and beautiful without sugar-coating things. Humanity supersedes the darkness.

RA: That was a necessity for my own survival. As I was writing, the pandemic started, and I was, like, Well, now I really need to go to the sweetness because I cannot survive this. I found myself gravitating toward the hope and the love and the way people are taking care of one another and the way that taking care of somebody in a tiny moment can feel like it will carry you for months or years. That little transaction might be enough even if it feels like the world is coming apart all around us.

That was why I wrote the book: to be able to look at the changing planet in a serious way and in a way that felt like there was a thread of light. It’s not exactly hope because nothing about the planet looks better at the end of the book. Pressing those two truths together — that things can be really bleak and scary and that we can love each other so much as our complicated, imperfect, growing selves — feels like the place where hope is, without pretending like any of the hard stuff is any less hard.

Jenny Slate: Even though there’s a lot of science in The Last Animal, it made me think a lot about the most unscientific thing in the world: fate. How much were you thinking about that while writing?

RA: These daughters haven’t chosen their fate — they were born, they had these two parents, they followed their dad around for his work in their early years, and just as their mom’s career took precedence in the family, he died. Everything is disorienting, nothing makes any sense, and the fate they tried to build for themselves turns out not to have worked out. From a writer’s perspective, that felt like a good situation for this strange new creature to appear in. It made emotional, logical sense.

There’s also something a little bratty about it, like, Oh yeah, universe? You’re gonna throw us all the hardest possible shit there is? We’re gonna ask a question of the world and see what it turns into. That’s the feeling I remember about being a teenager.

JS: I love how, in the book, there’s not just a “go” button for that. There is chaos, but there’s still process. Creating this creature is complicated, and they can only do it because Jane can figure it out. It’s not just “The world is weird and anything can happen.” There’s infrastructure here. Things are deeply unexpected, but there’s science, learning, and personal growth.

RA: When I started studying fiction, one of my friends turned in a story where all the babysitters in this little town got pregnant at the same time. I remember being, like, Wait, this is amazing. We can do this? Aimee Bender talks about the connection between magic and logic: Any strange event has to be intricately built out of logic. The more these things are connected, the more it gets back to what’s emotionally true. Even as Eve and Vera’s teenage hearts are all aflame from every injustice and everything that’s confusing, the world still has walls. You’re still responsible for your own choices and your own body in a world that does have consequences and works in reality. As a teenager, that’s a little bit disappointing.

The book is told largely from the perspective of Vera, who’s 13, but it doesn’t read like a young-adult novel. What went into the decision to narrate it from her point of view?

RA: For a long time, it was written in the third person and jumped between all three. Pretty late into the process, my editor suggested it could just be one of the girls. The character who understands the least is often the best narrator because they have the most to figure out. If you’re with the person who knows everything already, they’re just bossy or boring, so it completely opened the story once it belonged to the girls. Vera is the one with the most questions and uncertainty. I also loved the way she was developing on the page as somebody who’s both the wisest and the least informed. I felt close to her right away. She inherited thoughts that had once been written for an adult.

JS: What a huge adjustment. It can feel really good to cut and change things in a draft. There’s a lot of rearrangement in my editing process. I hang on to everything for so long, and when I finally un-grip, it’s a great relief. It feels good to mess it up and realize that I still exist, the work still exists, I didn’t set it on fire and erase my memory. I’m just changing the form. Things are really resilient, and a lot of times writing is asking for you to change it.

RA: And the spirit of all those early pieces, everything you might cut or move, is alive in there. It doesn’t disappear just because you’ve taken the sentence away. It needed to be there to begin with because that’s how you figured out what you wanted to say. And then you can take it away and trust that it’s full of that thing on its own. Plus, you can love something that’s in transformation.

You two have very different modes of creative writing. Where do you think your approaches to storytelling overlap?

JS: I don’t write fiction, but I tend to write about my experience using magical realism or the language of the psyche or the psychedelic. I’m always trying to figure out why I have this compulsion. Who cares if people know how I feel? I’ve always felt like I need to earn it. I try to fit the parts of my story that feel unattractive or hard or scary or that should be exiled from human experience into one sneaky vessel. I try to make my stories really inclusive and tasty and varied so I can be invited back and people will hopefully expect something intimate and new.

What I really love in The Last Animal is that there’s this asterisk shape of stories and they all meet in the center, which is this story of Jane and her girls. In the book, you can be with all of those stories at the same time. I live with the ghostly stories of my ancestors, and some of it is shocking and terrible, and some of it is natural and still weirdly sad. As I’m making my life now and I have my daughter, we could do anything. We could be dissimilar to the lives of my ancestors. While it’s a state of being, it’s not really a burden.

RA: When I’m writing a story, it’s never just about the story. It’s about all the ways the story has been told to me as the writer or to those characters. They’ve inherited something that precedes them, sometimes by many generations. The more the DNA of the old stories gets brought up to the new stories, the richer and deeper it is. I can never just tell one story. So having those other tucked-in fairy tales or fables or generational transmissions in The Last Animal is part of how I do that. The perspective and the way we shape ourselves by retelling those stories feel really critical to understanding who somebody is.

The biggest overlap I felt is that you both have come up with these fictional creatures whose stories are surprisingly heart-wrenching. What draws you to nonhuman characters?

RA: My heart changes pace as soon as I start thinking about some creature that’s vulnerable and small or feels alien in some way or doesn’t have a safe home in their universe. I instantly care, and it turns up the volume on everything else that goes on around them. There’s concern and fear and love and hope and need, all immediately in the scene, even if nothing else has happened. There’s this fresh set of eyes that is unbiased and clean and openhearted. They’re looking back at me, and I want to know what they see.

JS: There’s something about writing a creature that draws a line between what I want, which is to be intimate, and what I do not want, which is to take everything so fucking personally. If a dog walked into my front yard right now and took a shit in front of my house, I wouldn’t be like, Well, that’s a comment on me. I would just be like, Oh, that’s a dog. It’s not a referendum on my whole worthiness.

When you write an animal or inanimate object, people have a lot more patience and can suspend their disbelief a bit more. I want to put something out there that lets the audience relieve themselves of the connotations they’ll put on a human. With Marcel, for example, you’re continuing to learn about him throughout the short films and the movie, and after a while, you can feel what a waste of your time it would be to make assumptions about him, how much more worth your time it would be to wait and listen to what’s going on with him and let there be unknowns. Once you experience that with an animal or a created creature, I like to think maybe you would bring that to the real people in your life. And to yourself.

RA: We’re all those little creatures! We’re all delicate, misunderstood, and trying to translate ourselves into the world.

This interview has been edited and condensed.