This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Students and faculty returned to the University of Notre Dame campus for the fall semester as the state of Indiana was gearing up to implement a near-total abortion ban. The Supreme Court’s conservative majority, including South Bend’s own Amy Coney Barrett, had just overturned Roe v. Wade in June. The rollback of women’s rights weighed heavily on Tamara Kay’s mind when she learned that a student had been assaulted in August. Kay, a sociology and global-affairs professor who is both Catholic and a vocal supporter of abortion rights, thought of her time as a rape crisis counselor during her undergraduate days. “When people called the 24-hour hotline, one of the first questions they often asked was, ‘What if I’m pregnant?’” she recalls. She looked into what kind of support faculty could offer the student and was horrified that the school’s health clinic wouldn’t offer emergency contraception to sexual-assault victims.

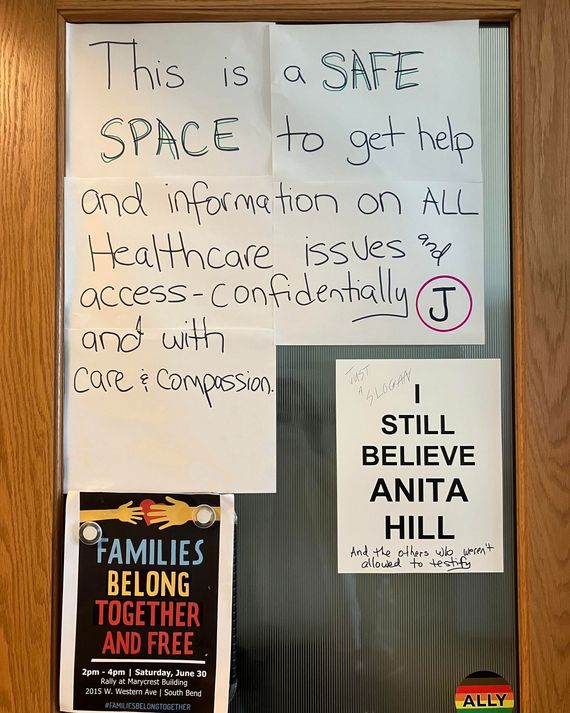

Angry and scared for the young women on campus, Kay decided that she needed to do something. On a warm Thursday evening in September, she put up a poster on her office door reading, “This is a SAFE SPACE to get help and information on ALL Healthcare issues and access — confidentially with care and compassion.” The sign was up for ten days. Then, in mid-October, a single deceptive headline appeared in a conservative student publication that would set in motion a monthslong campaign of harassment against Kay. “Keough School Professor Offers Abortion Access to Students,” blared The Irish Rover. The article spread like wildfire in the right-wing media ecosystem.

The messages Kay received online and in the mail at her office afterward were vicious and violent. “Drop dead cunt.” “Eat a couple of handfuls of opossum shit.” “Do you have a favorite abortion, or do you love all your abortions equally?” “Tamara Kay should be ass fucked under Touchdown Jesus at noon.” Kay reached out to the university for support, but she says Notre Dame administrators didn’t take adequate security measures to help curb the harassment. At a recent meeting to discuss her experience, Kay says, the university provost implied that she should expect people to be angry at her because of her abortion research and said there was not much the school could do about it. “I’m just running on sadness and feeling like the situation is hopeless, that they really just don’t want to help me and fix the situation and protect me or anyone else,” Kay says.

In a statement, a university spokesperson denied that the school had failed to address Kay’s security concerns or limited her academic freedom in any way. He said that Kay’s recollections of meetings described in this piece were “categorically false” and claimed that Kay did not adopt email protocols recommended to her. “There have been multiple meetings with Professor Kay and senior members of the University administration, in addition to meetings with Notre Dame’s police chief and multiple police officers, during which Professor Kay’s safety concerns were addressed point by point,” the statement said. “In all, it is patently false to claim that Notre Dame has done nothing to protect her.”

In some swaths of post-Roe America, even sharing basic information about abortion has become fraught. Not content with successfully overturning the constitutional right to abortion, the anti-choice movement introduced legislation in several states to block abortion-related websites. Around the same time the harassment against Kay began, the University of Idaho issued a memo to staff suggesting that speech around abortion, and even birth control, would violate state law except in very limited circumstances. Pro-choice faculty on conservative or religious campuses, like Kay, are the ripe targets for abortion foes.

In Indiana, abortion remains legal up to 22 weeks after the last menstrual cycle while the state ban is challenged in court. Notre Dame’s official stance on abortion since 2010 has been that the university “recognizes and upholds the sanctity of human life from conception to natural death.” Its student health-insurance plan does not cover morning-after pills or certain IUDs, and condoms are not available to purchase in campus facilities.

While abortion has always been a contentious topic at the school, Kay says Notre Dame knew of her award-winning work on the subject when she was hired six years ago. “It’s front and center on my CV, and I really didn’t want to accept a position at a university where my position on abortion would be a problem,” she says. The administration reassured her that academic freedom was sacrosanct, she recalls, and that she’d be able to pursue whatever line of research she was interested in.

Kay didn’t encounter resistance until she and her colleague Susan Ostermann began publishing op-eds in favor of abortion rights following the leak of a draft of the Dobbs decision in May. Their work appeared in Salon, the Los Angeles Times, and the Daily Beast. After the pieces were promoted through the official Notre Dame media channels, anti-abortion members of the university community complained to the administration. Ostermann says both of them received “nasty” emails as a result of their writing; shortly after, the school stopped promoting any sort of writing about abortion rights, whether in favor of or against them.

The same day Indiana’s ban initially took effect in September, Kay put the poster on her door. It included her personal contact information and instructed students to look for the letter “J” on the doors of other supportive faculty members. “There were faculty who thought, Oh my God, there’s going to be an abortion ban. We have high rates of STIs … We’re going to have pregnant students,” Kay recalls. “What are we allowed to tell them? What are we allowed to do?”

Several faculty members I spoke with say that after the Supreme Court’s decision, the school didn’t offer them any guidance on what they were allowed to say or do when it came to abortion. In a statement, the university’s president, Reverent John I. Jenkins, merely reiterated the school’s commitment to the “sanctity of all human life.” After putting the sign on her door, Kay texted a picture of it to the chair of the sociology department and asked if she was in violation of any school policy. He responded that he didn’t see any issue with it.

Six days later, Kay participated in a panel discussion on campus about the impact of Dobbs. When the event ended, The Irish Rover’s editor-in-chief, W. Joseph DeReuil, approached her. “He introduced himself and he asked me a couple questions. There was a lot of noise and a ton of people,” Kay says. “He did not say he was writing a story. He did not say he was interviewing me.” Neither Kay nor Ostermann, who was standing next to her, recall seeing DeReuil holding a recording device or taking notes. Neither remember him asking Kay about the sign on her door, either. “We thought we were having a nice conversation with this kid who we knew didn’t agree with our position, but seemed to be open,” she says.

For his part, DeReuil claims he asked Kay if she would comment on a story he was working on for the Rover. He tells me he’s been “disheartened” to hear about the harassment she’s experienced. “Regardless of what she’s saying, I don’t think that is an appropriate response,” he says.

After Dobbs, Kay frequently tweeted about medication abortion and emergency contraception and shared links to informative resources such as Plan C and the abortion-pills-by-mail provider Aid Access. She also posted that, in her character as a private citizen, she could help with access to or defraying the cost of the morning-after pill. In late September, Maura Ryan, associate provost for faculty affairs, and R. Scott Appleby, the dean of the Keough School, where Kay teaches, asked her to meet. When she asked what the agenda would be, Appleby said they’d like to discuss her “high-impact social-media presence.”

“They basically said, ‘We’re getting these complaints from your Twitter and the note on your door. We’re really concerned about liability, the appearance that you’re giving medical advice,’” Kay recalls. Kay volunteered to remove the poster and delete the tweets. In a letter recapping the meeting, Ryan wrote that she had asked Kay to “discontinue offering medical advice (in person or on-line) to students.” Kay was blindsided by that description. No student reached out to her for help during the ten days that the sign was up, nor have any contacted her since.

The spokesman for Notre Dame said the school “would never tell faculty, students, or staff what they can or can’t say about abortion or any other topic.” In the case of the sign on Kay’s door, however, the spokesman said “a reasonable person could understand Professor Kay to be giving medical advice (on becoming ‘unpregnant’ by taking abortion pills without knowing any details about an individual student’s health). This seemed unwise from both the perspective of faculty members and students.”

Kay found out that DeReuil had published his piece two weeks after that meeting, when she began receiving hate mail. “They would put in it, ‘If the Irish Rover story is true, you should resign, demon,’” she says. Her writing on abortion had previously put her in the crosshairs of the publication, but this piece, which falsely claimed Kay was working “to bring abortion to Notre Dame students” and distorted her comments at the September panel, quickly boomeranged through conservative media. A rogue liberal professor offering to procure abortion pills for students at a Catholic school was too good a yarn for Breitbart, the Daily Wire, the Daily Caller, National Review, and Fox News to resist.

Threats and hate speech overwhelmed Kay’s inbox for weeks. A letter signed “Notre Dame alum” was left on her office door that read in part: “I am glad someone at Notre Dame is ensuring women get abortions. Especially for ugly and/or fat women; we don’t want too many of them passing along their genes. All praise Moloch!” The Sycamore Trust, an alumni organization whose mission is “protecting Notre Dame’s Catholic identity,” published several newsletters railing against Kay’s “pro-abortion campaign.” It also sent two letters to Provost Dr. John T. McGreevy, Notre Dame’s chief academic officer, one of which read, “We hope that, one way or another and before too long, she will move on to a school where she will not feel compelled to subvert its deeply held convictions of conscience.”

Kay worried that someone would act on the threats she was receiving and grew concerned for her family’s safety. She disconnected her office phone. She gave up her parking space and didn’t come to campus, afraid that her colleagues would be harmed if someone came after her. “People can say outrageous things, even if they don’t intend to act on them, but you just don’t know. So you have to take them all very seriously,” Kay says. “That just creates this constant vigilance. My heart starts pounding when I get near my office door to check and see if anyone’s attached something to the door. When I’m told a package arrives, ‘Okay, what does it look like? Who’s it from?’”

Her house appeared to be vandalized several times, further rattling her. “On Christmas, it snowed here. Someone peed on our porch. There were no animal tracks, it was boot tracks,” she says. “This other thing happened with garbage on the front of our porch. We started keeping the porch light on. There’s a lot of checking doors at night.” Kay emailed her neighbors to ask if they were experiencing disturbances too; no one had.

Kay regularly forwarded the emails she received to her direct supervisors and other administrators. She also shared her concerns that the harassment was coming not only from outsiders, but members of the university community. She asked for a safety plan, including protocols to deal with the mail she received on campus and to be relocated to another classroom. She shared some of the correspondence she received with the Notre Dame Police Department, which monitors specific threats that she forwards to them. They also came to her home to do a security assessment, a copy of which Kay only received months later, after the Cut contacted Notre Dame.

“I thought the university should have responded with empathy,” Kay says. Instead, administrators respond to her emails sporadically, and the university hasn’t authorized campus police to investigate who’s behind the harassing emails. She compares her experience to that of one of her colleagues at the University of California, Berkeley. “She got death threats from a student and Berkeley paid to have a security system installed in their home,” she says. “This is a public institution. They took it seriously. And this was a one-off event. It wasn’t ongoing.”

The situation worsened in early December, when Kay and Ostermann published an op-ed in the Chicago Tribune debunking common misinformation about abortion care. The op-ed included a disclaimer stating that the authors’ views didn’t represent those of Notre Dame. Nevertheless, Reverend Jenkins sent a letter to the editor the following day that said the op-ed “does not reflect the views and values of the University of Notre Dame in its tone, arguments or assertions.” It was unprecedented for the president of the university to respond publicly to the writing of faculty members, and her colleagues described it as the president signaling to abortion foes that it could be “open season” on Kay and Ostermann. “It just bothered me that other faculty expressed their opinions on contentious issues, and he has remained silent,” says one faculty member, who spoke anonymously out of fear of professional retaliation. When the shooter who killed ten Black people at a Buffalo grocery store last year approvingly cited the writing of a Notre Dame professor in his white-supremacist manifesto, the school issued a statement that didn’t condemn the contents of the article.

The faculty members I spoke with described a cadre of administrators, faculty, alumni, and students that view Notre Dame as the last great Catholic institution in the country. These diehards urgently seek to preserve what they believe to be the university’s identity when it comes to issues like abortion and LGBTQ+ rights, the faculty members say, and so they’ve trained their sights on Kay. Her experience has already had a chilling effect on other faculty members. “There’s this growing perception, not just that the school may not support you, but also that because we are at Notre Dame, we may be more susceptible to being attacked by certain right-wing individuals or groups,” says Elizabeth McClintock, an associate professor of sociology who has been teaching at the school for over a decade. She says she’s spoken with colleagues who are choosing not to publicize their research due to fear of backlash, or who are nervous about upcoming tenure reviews because their areas of study potentially conflict with Catholic Church teachings. “In theory, that shouldn’t be relevant,” McClintock says. “And I don’t know if it will be relevant, but the point is that people are now nervous about it.”

Kay taught her final class of the fall semester with a plainclothes campus police officer standing guard outside her classroom. In December, she hired a lawyer to pressure the university into taking her security concerns seriously and to protect herself against any potential retaliation. That same month, the Sycamore Trust mailed a postcard to alumni and others across the country with a picture of the sign in Kay’s door, in which her name, personal email address, and office number were visible. The postcard repeated the falsehood that the sign signaled “to Notre Dame students that she will help them obtain an abortion,” while also condemning Jenkins for giving Kay a “prominent platform” as an expert on abortion rights.

Ostermann, Kay’s writing partner, tells me she expected they would receive some pushback once they began publishing after the Dobbs leak. “We’re both in a policy school, and we’re supposed to engage with and to write about highly political issues,” she says. While she has received hate mail, she says it’s been a fraction of the harassment Kay has experienced. “Whatever risks I take are about me, but she’s in a different position because she’s a mother,” Ostermann says. She’s grown concerned about her friend’s well-being. “Tamara has always been so smiley, so bubbly. She hasn’t fallen apart over this, but she has come close.”

The brilliance of a bad-faith harassment campaign is that it renders the subject unable to distinguish between a real threat and an offensive email the sender forgets as soon as they write it. Kay says most of her students and colleagues have shown her support; for every threat, there’s been an email thanking her for not cowering to the forces that would rather she be silent on abortion rights. But she now assesses every interaction, weighs every scenario, in a way she didn’t have to just a few months ago. Would the people telling her to die show up to her classroom to harm her? She can’t rule out the possibility. Would students planted in her future classes go on to publish stories that take what she says on contentious topics out of context? That’s a fear Kay and other faculty members, seeing what she has experienced, now share. Would people set traps to try to get her fired? Shortly before the Rover piece was published, a young woman at neighboring Holy Cross College, whose affiliation with an anti-abortion student group was spelled out in her email signature, wrote Kay asking for help “getting Plan C.” Kay didn’t respond, seeing it as a gotcha moment. What if next time the sting isn’t so obvious?

Kay’s family is now more careful with their comings and goings and hypervigilant about their surroundings. She’s taken down her Twitter account and parts of her website after they expressed concern about the risks of her online presence. Some of her closest friends have urged her to leave her home and stay elsewhere for the time being, but the family’s savings have taken a hit from the cost of retaining a lawyer. A group of Kay’s colleagues have organized a GoFundMe to help with her legal costs.

Some of the faculty believe the administration has done little to help Kay in hopes that she becomes so miserable that she walks away. “My impression is that they’re just trying to make her leave,” says the faculty member who expressed concerns about Jenkins’s letter to the editor. In late February, Kay was finally able to meet with the university provost, Dr. McGreevy, albeit without her lawyer present. It quickly went downhill, she says; McGreevy accused her of failing to respond to the administration’s and police’s purported attempts to help her navigate the situation. When Kay shared she has an upcoming research project on the impact of abortion bans, she says he responded, “Well, Tamara, if you are going to continue, if this is going to be the focus of your future research continuing on this issue, then you need to know that this is a Catholic university and there are going to be people who are not happy with that.” Kay says the conversation ended without any resolution, and other than a letter recapping the meeting, she hasn’t heard from administrators since.

The impasse has left Kay feeling trapped in South Bend. She is on a preplanned sabbatical for the spring semester while she works on her third book. Friends have told her she needs to leave Notre Dame, but job prospects are hard to come by for a tenured academic. If her life were different, she muses, maybe she’d quit. “I lived on $13,000 a year at Berkeley. I know how to do it,” she says. “But you can’t do that when you have a family.”

She’s tried to put her head down and keep working, including writing new op-eds about abortion. But recently, she found herself unable to sleep and anxiously anticipating another round of threats after The Irish Rover wrote about a talk she gave to the College Democrats that touched on abortion. “I started to feel, in the last few days, feelings I’ve never had before. And that terrified me,” she says. “You know, like real hopelessness.” She’s now weighing legal action against both the publication and the university. “I’m not a victim. I am an academic,” Kay says. “I’m an expert who has the ability to write about an issue that is incredibly important. All I’m trying to do is do my job.”