There is one thing Latinx writers tend to hear about our migration stories: They are too tragic. Too hard to wade through, too hard to digest, too complicated. The implication is that, if we want our stories to be read, we should produce work that’s more marketable, entertaining, and light.

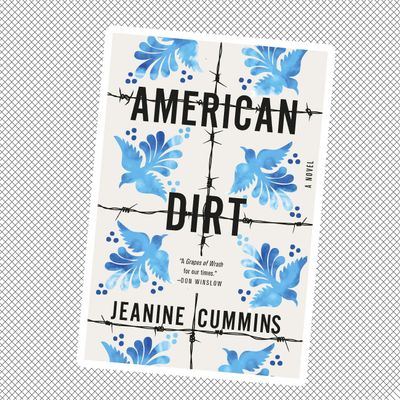

American Dirt by Jeanine Cummins, which was met with intense criticism when it was released last month, is just that. The novel follows Lydia, a thinly drawn Mexican woman who is forced to cross the border with her son after a cartel boss falls in love with her, massacres her family, and is so vengeful he won’t stop hunting her down. It’s a migration story as romance-thriller. According to famed spy novelist Ian Fleming, a thriller cannot contain anything that will weigh it down, and American Dirt lacks any kind of nuance, contextualization, and characterization that might impede its breathless plot. The book received a seven-figure advance, a movie deal, and an Oprah stamp of approval because it turns a hard-to-tell story into an easy one.

Border stories are complicated. They necessarily intersect with systemic oppression, racism, and the effects of the U.S. empire. But in American Dirt none of these things affect Lydia. She worries instead about one bad man. By reducing migration to interpersonal conflict, Cummins erases the border’s political context; the end result is a lighter, more digestible story.

There’s a reason that most people who go through the kind of traumatic events exploited by American Dirt choose not to write their stories as thrillers. Traumatic events have to be survived in the moment, and for many years after. Writing about past trauma is often a means of self-preservation. Thrillers are at cross-purposes with this: They require oversimplification and demand a source of exhilaration. I have yet to meet someone who finds their own trauma exhilarating.

I came to the U.S. on a student visa in 2002. Growing up, my family in Colombia was persecuted by guerrillas, and we later fled to Venezuela. My sister and I grew up amid death and car bombs; she was later diagnosed with PTSD, and I was diagnosed with an anxiety disorder. We migrated many times before reaching the U.S., and as we moved from place to place, we coped by adopting various methods of self-harm. It took many more years before we were each able to begin making sense of these experiences and start to heal.

Once I arrived in the U.S., I stopped talking about my past. I didn’t want to be defined by a string of violent events I experienced in childhood. When friends asked about my life before I moved, I lied through omission. I came here to study, I told them. In reality, I landed in Chicago because my cousin lived there, and I had no prospects and no home to return to. When things are too terrible to speak out loud, they often go unspoken. Eventually, I had no other recourse but to write. But I was not courageously breaking silence: I was caving to a great need to speak.

Think about the worst thing you’ve ever lived through, and then imagine returning to it, diving into it again and again, over the course of years. That is what it’s like to write about past trauma. It is difficult to dwell down there, where it feels like you’re running out of air, where it feels like you might drown. The pressure is too high. The deep end, my friend the poet Tongo Eisen-Martin calls it. Trauma is a bottomless place, and I’ve spent my time down in it. Novels take years to craft; mine took seven. It is inconceivable to me that I could have worried about the digestibility of my experience. It was the other way around: I was fighting for it not to digest me.

Unsurprisingly, silence emerged as a central theme in my novel. My characters, like my family members, were plagued by different forms of silence: the kind born from shame, survivor’s guilt, or simply the need to protect oneself from pain. The story is told through two alternating voices: Chula, a 15-year-old refugee living in the U.S., and Petrona, a 22-year-old who worked as a maid for Chula’s family, and was never able to escape the dangers of Colombia. In the same way that the weight of my silence was forcing me to write, the silence surrounding their experiences eventually forces them to think back on how they met and the secrets they kept together. In American Dirt, the border crossing is the point; there’s little before and no after. But I wanted to focus on what happens after the migration, after the trauma. I examined the ways in which my characters were able to create the joy and levity that allowed them to survive.

After I sold my novel and was waiting for it to come out, I taught writing to a group of documented and undocumented immigrant high-school students in San Francisco. Five times a week, for an hour, I held space for their stories and for their silence. Some days we wrote, crafting poems about the smells and sights of our homelands, phrases that we kept close to our hearts like mantras. Other days I taught them a different form of expression: painting, collage, photography. I told them funny stories about my family. They made fun of my music taste, speculated on whether I was goth, asked about my love life. We talked about Trump. When they began to write directly about their experiences, as most of them eventually did, a hush would fall over the room. One kind of silence made way for another.

Most books about migration are heavy because the experiences are heavy. They are not thrillers, because how could we, after actually living through the pain and fear, find any thrill in it? If we include violence, it is there because we have weighed the risk of spectacle against the importance of not looking away.

American Dirt has been called trauma porn, and critics have noted that Cummins devotes little space to characterizing Mexico and Mexicans, but instead fills her pages with exploitative, shallow depictions of the suffering her characters endure. She titillates her readers with lengthy descriptions of graphic violence and uses the gratuitous deaths of migrants to create tension. For example, young boys are constantly jumping onto moving trains to get closer to the U.S. border, and when they do, their limbs dangle precariously over the tracks each time. This culminates in a scene in which a man trying to reach the border jumps onto a moving train and falls to his death. When at last his grip fails and he falls, Cummins writes, “The man is sucked instantly beneath the wheels of the beast. His mangled screams can be heard above the sounds of the churning train.” The man’s death and the foreshadowing leading up to it seem like little more than page-turning devices.

Despite Cummins’s assertion that American Dirt was a unique migration story, of the kind that we “never get to hear” and one she wished “someone slightly browner than me would write,” the truth is authors who are personally intimate with border crossings already have penned them, with more grace and brilliance, and their skin color has nothing to do with it. Javier Zamora’s 2017 book of poetry Unaccompanied asks: Is fleeing from danger a crime? Instead of depicting the violence or desperation of a desert crossing, Zamora turns his attention to the trees, animals, and wind at the border, which only makes the unseen violence louder. The playwright Octavio Solis structures his 2018 memoir Retablos, about growing up along the border, as a series of vignettes, detailing events both joyous and difficult in turn. Valeria Luiselli’s 2017 book-length essay Tell Me How It Ends is arranged around the 40 questions that asylum-seekers must answer in order to qualify for refuge in the U.S. These are books in which subjects’ humanity is not only not questioned, but inherently understood, and endlessly complicated.

When the publishing industry — which is 84 percent white — tells Latinx writers that our stories are too hard to read, our worlds too complicated, our audiences too small, do they not mean this is hard for me to read, this book doesn’t reach me, it is difficult for me to bear witness to what my people have done, I don’t see myself in this story? Despite all its failings, American Dirt still made its debut at No. 1 on the New York Times Best Sellers list. Writers like Cummins will continue to supply these voyeuristic stories for the white imagination. And we will continue telling our stories as is natural for us to tell them.