Three years ago, after finishing a novel about mother-daughter relationships, author Edan Lepucki put out a call on social media for photos of her followers’ moms from before they were mothers. “I wasn’t prepared,” Lepucki later wrote, “for how powerful the images I received would be.” She soon started an Instagram account dedicated to the project, which now boasts 77,000 followers and nearly 700 posts, each depicting a woman pre-motherhood, along with a caption from her daughter. So popular was the collection that it has taken on a second life as a book, Mothers Before. In it, Lepucki has amassed over 60 essays and photographs exploring the complicated, moving, inspiring, multidimensional lives women have before they take on the identity of “mother.”

Here, find an excerpt from Mothers Before, out now from Abrams.

This is my mom, Elisha, at her junior prom back in 1988. She was seventeen. One of the biggest songs that year was “My Prerogative” by Bobby Brown, and I can only imagine her feeling the beat by swaying her hips and snapping her fingers. I like to think she and her date, Johnny, cut it up on the dance floor.

I’m mesmerized by her electric smile in this picture. Her dimples are so pretty. She looks so innocent. But I know this seemingly carefree teenager had already seen so much darkness and known far too much pain. She would have already experienced sexual abuse numerous times and had been the victim of an abduction. It sounds like too much to comprehend, let alone to live out. Her life in those first seventeen years was much more complicated than it should have been.

But then again, that electric smile sums up exactly who my mother is: a superwoman with unparalleled courage and strength. That, despite the horrific experiences behind her and the fear of the unknown in front of her, she was determined to change the narrative of her story. She’s still smiling today, and wider than ever, because she did manage to change that story. I couldn’t be any prouder of her for it.

—Jasmin Pettaway-Solano

Everyone who knew my parents saw the easy romance they shared for forty-one years before my dad died of Lewy body dementia. My mom used to leave my dad notes and sign them with a doodle of a character she’d made up called Boog. In her wallet, she still carries a small card he made her that reads, “This card is good for an unlimited supply of ‘I Love Yous.’” Walking behind them meant I’d probably have to see his hand over the back pocket of her jeans, so I often upped my pace. In most photographs from my childhood, their toothy smiles shine as they stand shoulder to shoulder behind me and my sister. In one of my favorites, they’re slow dancing at a wedding: hands intertwined, eyes locked. In another, they’re laughing as they hold up plastic cups of water to celebrate the end of a successful river-rafting trip.

In this picture, taken in 1966 while at San Diego State, my mom smiles at her college boyfriend. When I found the picture and asked about the guy in the white T-shirt, she said, “What’s to say? We dated for a couple years. I was never in love with him.” I’m fascinated by how this photo differs from so many taken of my parents. It’s the overall dullness of her expression that I find most striking—her lukewarm smile and blank gaze, so unlike the enthusiastic and tender way she looked at my dad.

He’s been gone seven years now. When my mom’s friends encourage her to date, she says she had her love and it was true.

—Kristen Daniels

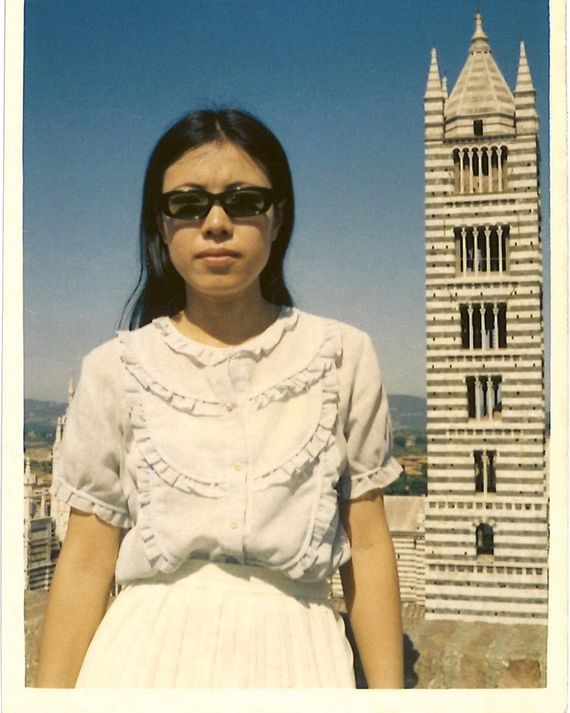

Here is my mom, at around twenty-one, studying opera in Italy. It’s 1965 or ’66. She’s one of very few Japanese girls to have left her country and gone to Europe. See the confidence and style? She learned German, Italian, and French. She will forgo her career and turn her energy to me. She will teach me everything she can about her homeland, about beauty and art, and she will tell me every day, no matter how sick she becomes—and she becomes very sick—to never to give up.

—Marie Mutsuki Mockett

The year is 1967. This is just before she met my father, before she had us three kids. It’s a photo of before, but in truth it’s also a photo of after. At twenty-seven, she is no ingenue, at the start of her journey. She looks already knowing, a little tarnished. She has already crammed in so much life. She has already made some major mistakes, with flair.

She has already gone west for college—and dropped out of college. She has already been married—and divorced. She has written and published two books of pulp fiction under a pseudonym—and has begun to write her first real literary novel. She has been voted Slum Goddess of the Lower East Side and dated pretty boy Eric Anderson, star of Andy Warhol’s film Safe; she broke up with him after he slipped hallucinogens into her drink and sent her on a twenty-four-hour bad acid trip. She has already gone south in the summer of 1966 to report for CORE on civil rights violations.

It takes work to find a patch of light outside my mother’s shadow. Her stories, their myth-making quality, always leave me with this weary, jaded feeling, as if they happened to me. Women of her generation, I sometimes think, drank all the freedom juice, leaving none for their daughters. They lived so hard and so relentlessly that we, their children, have grown up skittish, cautious, demure, hemmed in. At the park one day with my own kids, a mother friend tells me about a game called: What Would Your ’70s Mother Do? It’s an internet meme, a caution against helicopter parenting. It becomes a mantra between me and this friend after that. We say it over and over, laughing, trying to will ourselves to be as careless as our seventies mothers, so that we, too, will raise resilient, self-reliant children. We, too, want to chain-smoke and drag our children to protests and let them climb, unbelted, into the back space of the station wagon. We want our babies to suck on marbles and survive. We want to plow through lovers and multiple divorces. We want to care more for friendship than we do for romance. But we know even as we say it—What Would Your ’70s Mother Do?—that it’s too late for us; we know too much.

August 1967. Sometime after the bad drug trip, my mother left the Bowery. Moved back to her childhood home in Cambridge, along with the dog she called Woofer, a rescue from the Lower East Side SPCA. Her father was dead, and so was JFK. A friend, Laurence Scott, took this photograph. “This would have been before I met your father,” she tells me of the photo. “The way I look in that photo is the way I felt,” she says. “Lost.” But what I like about the picture is that she doesn’t look lost at all. She looks pissed off, a little louche, fired up and ready for more.

—Danzy Senna

Excerpt from the new book MOTHERS BEFORE: Stories and Portraits of Our Mothers as We Never Saw Them collected and edited by Edan Lepucki.

Copyright © 2020 Edan Lepucki. Text/photo credit: © MARIE MUTSUKI MOCKETT. Text/photo credit: © JASMIN PETTAWAY-SOLANO. Text/photo credit: © KRISTEN DANIELS. Text/photo credit: © DANZY SENNA. By permission of Abrams Image, an imprint of ABRAMS, New York, NY. All rights reserved.

A few weeks into social distancing, the Cut’s Jen Gann spoke to Mothers Before editor Edan Lepucki about parental worries and writing modes. An edited and condensed version of their conversation is below.

I’m curious: Have you thought about how your own kids might contribute to a project like Mothers Before someday?

Oh, all the time! I’m a little bit haunted by the idea. I think every parent probably wonders, “What exactly am I doing right now that is going to mess them up?” and “What is the thing that I don’t even realize they’re going to be talking about in therapy?” and “What is their idea of me as a mother and what is part of the legend that they’re accumulating about me from before I became their mom?”

My daughter is only four and my son doesn’t seem to care at all, but my daughter has just started to ask questions like, “What did you like to do when you were my age?” Just a week before the book came out she asked me to show her pictures of myself from when I was her age. It was really sweet. So, I’m both a little bit paranoid that I’m not doing everything the way that I hope I’m doing it and also kind of excited by the prospect of them eventually digging into “What was mom like before we came along?” because I think that I’m pretty much the same. I don’t think there’s a clean break between my before-motherhood and after-motherhood, and I’m excited and hopeful that they’ll see that as well.

As a fiction writer, how did it feel to switch gears for this?

It was a great relief! I mean, at first it was just me emailing either writers that I knew or writers that I really admire or trying to find celebrities to email me back (they never did). Once I got the writers that I really admired or knew or wanted to be a part of the book, then it was waiting for them to get back to me. And because they’re such good writers, I didn’t have any heavy-duty surgery to do on the pieces.

There weren’t any points when I was like, “Okay, I can’t do this,” whereas with fiction, you have to create something out of nothing and it can be very lonely. This is much more interactive. It was just a joy to get these little essays in my inbox every few weeks.

If you buy something through our links, New York may earn an affiliate commission.