I had just turned twenty-one when I got the call that I had been cast in a John Legend music video. It was 2005, almost a decade before Time magazine announced the “Transgender Tipping Point,” and no one — not John, not even my agent — knew my history. They couldn’t know. The modeling world was no place for an out trans woman. Not yet anyway. But I said yes, knowing I would have to hide — again.

Back in the Philippines, where I was born and raised, it would have been impossible for me to keep a low profile. On the other side of the Pacific, I was a celebrity — the most famous transgender beauty queen in a country of over 75 million people. I started performing when I was fifteen, frequently competing on nationally televised pageants, earning the top prize again and again.

Just five years before I got the call from John Legend’s team — and only months before I moved to the United States — I had won the Miss Gay Universe crown, a prestigious prize in the Philippines trans pageant scene.

In New York, I kept my pageant past a secret from everyone I worked with. I wanted to be successful without getting outed, which felt like driving right up to the edge of a cliff before slamming on the brakes. In 2005 I was rising through the modeling ranks, but no one had dug into my past yet, and I wanted to keep it that way. I might have been out and proud in Asia, but here in America, I had to be in the closet.

You might think it would have been the other way around. The Philippines has a reputation for being a conservative Catholic country — and it is. We have centuries of Spanish rule to thank for that. But as journalist Carmen Guerrero Nakpil famously said, the Philippines spent “300 years in the convent and 50 years in Hollywood.” We embrace spectacle and theatricality with open arms. When I was growing up, Catholicism and trans beauty pageants inspired equal fanaticism. Families would go straight from mass to watching the Super Sireyna trans pageants on TV back at home. No one really saw this as a contradiction; it was just part of our unique cultural blend.

If social media had been big back in 2005, I would have been screwed. Someone from the Philippines could have posted a clip of me to YouTube or shared a pageant photo on Instagram, and then everyone would have found out who I was. But in the time before Facebook or Twitter, I could live a dual existence, famous overseas and a nobody in New York.

Well, not exactly a nobody. My profile was rising. I was on the cover of magazines, appearing widely in lingerie and fashion advertising. A commercial I had shot the year before for Emerson Radio was playing in Times Square, and I’d appeared in an ad for Rimmel a few months earlier. As risky as they were, both were lifelong fantasies come true.

When I was dominating pageants in the Philippines, my mentor once showed me newspaper clippings of an international model named Caroline Cossey, better known as Tula, who had appeared in magazines like Harper’s Bazaar and been photographed for Playboy. Tula was transgender, but no one knew it — not at first anyway. She managed to keep her secret all throughout the 1970s. Her story was a legend in our community, passed down from generation to generation.

It was my dream to be like her one day. I wanted to be on billboards and in magazines. Tula’s face on that crinkled newspaper was proof that I could do it. Maybe I wanted to show that being trans couldn’t hold me back. Maybe I was vain — what aspiring model isn’t? But I think more than anything, I wanted to be seen.

Years later, with my face showing up in newsstands and fashion publications, I was more visible than ever. My successes should’ve made me happy. But the bigger my modeling job, the more crushing my anxiety became. Every camera lens felt as threatening as a loaded revolver. I was betting my livelihood on a roulette spin every time I accepted a high-profile assignment.

But a music video? And not just any video, but one for a hit song on a debut album that was getting Grammy buzz? That could get me real exposure, catapulting my career at a critical moment. As much as I was terrified of being found out, I couldn’t resist vying for that next level of prestige. I had already reached the pinnacle in one country — why not try for two? Breaking through in the United States would be hugely validating, not just of my looks but of everything I had sacrificed to get to this point: I had left my celebrity standing in the Philippines and my family and friends in California all to make it as a model in New York.

As I prepared for the shoot, I thought about all the women who had made names for themselves by starring in sexy music videos. I mean, everyone remembers the iconic trio of Naomi Campbell, Christy Turlington, and Linda Evangelista in George Michael’s video for “Freedom.” Helena Christensen’s role in the sensual black-and-white video for Chris Isaak’s “Wicked Game” sent her career into the stratosphere.

I wanted to follow in these women’s footsteps. They had cemented their place in pop culture by appearing as themselves. And yet I couldn’t be seen. Not fully.

In 1981 Tula was publicly outed in a British tabloid under the headline “James Bond Girl Was a Boy.” The ensuing uproar — outrage, disgust, contempt — drove her to the brink of suicide. I should have seen Tula’s story as a warning. Instead, with all the boldness of youth, I think I took it as a challenge. I wanted to go even further than she had, and then — though my vision for this was blurry at best — come out on my own terms.

But of course, the media of 2005 was no kinder to trans women than the media of 1981. If I valued my career, my safety, and my family’s privacy, I had to avoid Tula’s fate.

Ironically, I ended up dancing behind a curtain in the John Legend video. My body was on full display, but I was a silhouette. A shadow in lingerie. During takes, my moves were slow and deliberate. I tried to dance as sensually as I could, but each hair flip lengthened my neck, threatening to expose my Adam’s apple. What if the director zoomed in on it? Adrenaline surged through my body. My breathing sped up. It didn’t help that the smoke-filled set was frigid, despite the space heaters around us.

Between takes, a production assistant would rush over with a warm coat, but in truth, I was shaking because I was nervous. Still, I used the temperature as an excuse when the director asked how I was doing. He was friendly and chatty, but my survival instinct kicked in: instantly, I feminized myself, restructuring my whole being in a split second. “Hey Davy, how’s it going?” I said, shifting my voice into a high femme register. “What’s our next shot?”

After a few more takes on the John Legend video, the on-set stylist pulled me aside — “Geena, can you come with me, please?” — and led me toward an RV parked outside on the cobblestone streets of the Meatpacking District. The huge production lights made me feel like I was walking into an interrogation.

Do they know? Did the camera catch something? My mind was full of negative fantasy, always expecting the reckoning to come at any moment.

But when we got into the trailer, the stylist just wanted me to try on different color lingerie. I could breathe again. The adrenaline left my body all at once, draining me. I wanted to go home. We had started shooting at nine p.m., and it was already three a.m. But if I wanted my big break, I had to return to the lion’s den.

I convinced myself that if I was always careful, if I remained hypervigilant, I wouldn’t get clocked on the job. I can do this, I told myself as I pulled on the new lingerie, trying to be my own best friend, hyping myself up. But I felt so alone.

Back on set, I flicked my hands delicately, swaying my hips as I danced to the sensual R&B beat. The backlit shot made me look even more mysterious. And I was a mystery — to myself as much as to anyone else. I wanted to be seen for who I was, but that was not an option. And because I couldn’t let anyone else truly know me, I barely knew who I was anymore.

Sometimes I second-guessed my modeling dreams. Still, I found affirmation in the fullness of my feminine expression, where I felt my power. So many voices had told me to act a certain way, dress a certain way, think a certain way, be a certain way. Modeling was my way of trying to define my own womanhood — to free myself from those cages. The work was sometimes rote; posing for department store catalogs did little for my soul. But when I did shoots that felt more personal, that allowed me to say something with my body that could be captured for eternity, there was no substitute for the high I felt.

By the time I got home from the music video shoot, it was seven a.m. I crawled into bed, exhausted — a bone-deep fatigue that had nothing to do with the all-night shoot and everything to do with the stress I’d been living with for years, with no end in sight.

I wasn’t outed back in 2005. But the fear shaped my life for years to come. I had thought I was afraid of other people — the models, the photographers, the agents. Eventually I realized I was most afraid of myself. It had been so easy to hide behind the curtain of being stealth; if people didn’t like me, well, I wasn’t showing them the real me anyway. I buried myself beneath layers of internalized transphobia and self-loathing, and my paranoia had reduced me from a vibrant, proud, and unapologetic Filipina trans woman to a stranger. On my 30th birthday, as my gift to myself, I decided to finally go public with my identity. I freed myself.

Now, when I watch that music video on YouTube, where it has over six million views, it looks like the R&B gods were playing a trick on me. For the money shot, at the fifty-five-second mark, I part the curtain I’ve been dancing behind and gesture for John to get closer. Come hither, my whole body is saying. I had never felt more naked, physically and spiritually, than I did in that moment.

As the camera pans up to my face, bathed in sensual golden light, John sings, “Now who is she? What’s her name? You don’t need to know about everything.” For a long time, that’s what I believed, too. Until that belief no longer felt true enough to live by.

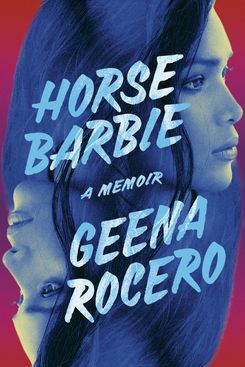

From the book Horse Barbie, by Geena Rocero. Copyright © 2023 by Geena Rocero. Published by the Dial Press, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.