This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

When Regina King presented for an awards show this past April in a strapless clementine-orange gown that melted onto the ground like just-cut sashimi, she looked like a beam of Technicolor. The dress was loud, vividly bringing out the warmth in her skin tone, and stiff, with folds that stuck up a little instead of lying flat. On a gray winter morning at his studio, the gown’s designer, Christopher John Rogers, told me that it was “made out of fabric similar to what firefighters wear. So it’s kind of off, it’s kind of weird.” The starchy utility twill gave it the insouciant feeling that it could be messed up and still be fine. But the dress was also lined with silk, boned with a mesh corset, and gracefully sewn. It reveled in the tension between delicacy and roughness.

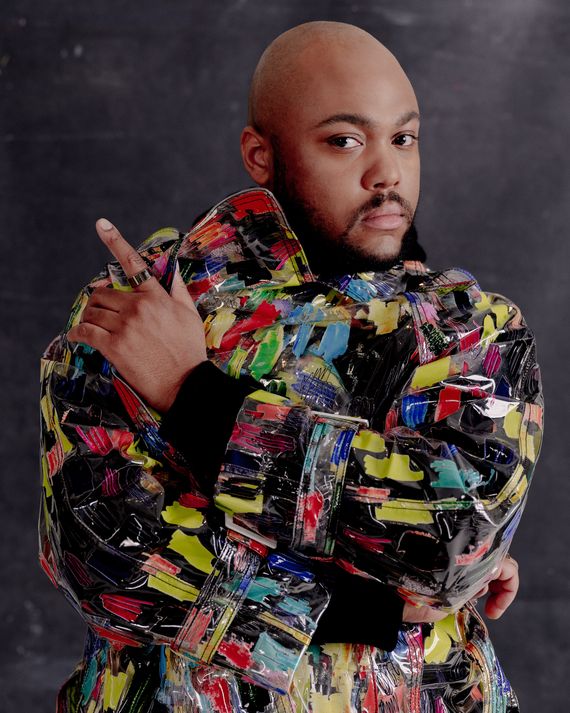

Rogers calls his aesthetic “pragmatic glamour,” a sensibility that merges the unreal and dramatic with practicality. At 28, he has become one of the most celebrated fashion designers in the industry; critics have said his work is exciting because of the way he makes uncomplicated but showstopping pieces. After winning the Council of Fashion Designers of America/Vogue Fashion Fund in 2019, the most coveted prize for emerging designers, Rogers went on to win the CFDA American Womenswear Designer of the Year Award late last year. It’s the kind of anointing that has sent some designers on to long and prominent careers and has, for others, represented a fleeting moment of recognition before the industry turned its attention elsewhere.

At the studio, Rogers was wearing his own aqua-blue polka-dot sweater with big ribbed cuffs, chunky gold rings, and blue nail polish. We spoke in a meeting room as he drank a giant Dunkin’ Donuts iced coffee; outside the glass doors were racks of clothing and his business partners’ desks. Rogers has a shaved head and bow mouth, and he grows a light beard that doesn’t manage to age him. He is both bubbly and a little shy; at his CFDA after-party, when his friends called him to the center of the dance floor, he did a small dip to a Beyoncé track in front of the cameras, then moved out of the spotlight. But once we started talking about his clothes, he became increasingly self-possessed.

Rogers says he is both a cerebral and an emotional designer, drawing from inspirations as disparate as vintage airport design, 1980s interiors, things hanging from telephone poles, and “feeling happy.” He’s inspired by objects with very specific colorways; recently, he had been fascinated by the mood of 1970s aspic dinners: plates of yellow or green Jell-O molds sitting next to meats and shrimp and mayo, their colors saturated and strange. He is known for his exquisitely cut gowns but loves working most with cotton, twill, and denim. He wants his customers to feel happy with themselves but not so precious about their clothes that they can’t throw them into a ball on the ground. He prefers clothes that have “crunch” — made with fabrics like silk faille and plastic coating; he’s interested in how “a crumpled carry-out bag might have the same energy as, like, an 18th-century gown that’s crumpled on the floor. It’s not about the gown, and it’s not about the bag: It’s about the thing in between them.” One of his most famous pieces, a pink plaid ballgown on display at the Costume Institute, was inspired by the look and feel of trash bags and curtains. If he could use paper, he would.

“For me, there’s no aesthetic hierarchy,” Rogers told me. “It’s just a dictionary. You can pick whatever you want, but everything is the same price, whether you’re referencing Sesame Street or an 18th-century painting. It’s what you do with the thing.” By mixing those mainstream and esoteric references with shameless opulence, Rogers is pushing the boundaries of how high fashion can look and where it can come from.

Rogers grew up in Baton Rouge, Louisiana’s capital city, on the eastern side of the Mississippi. His mother, Johnell, was a ballet dancer who became a medical technologist, and his father, Christopher, had studied photography and then worked in library technology. When his father went to his job at the Southern University library, Rogers would tag along and log on to the computers. As a boy, he was reserved, but the internet of the early aughts presented a refuge: He’d watch anime and research dinosaurs; he’d play Pokémon and dress up digital Barbies.

In the fourth grade, Rogers and his group of friends passed around a notepad and created their own comic books, and he discovered fashion design while drawing outfits for his characters. He didn’t feel comfortable asking his parents to buy him fashion magazines, but on the internet, he could find entire editorials from Elle and i-D that generous strangers had scanned and uploaded. He went on YouTube and watched the shows presenting the highly tailored, opulent clothes of Alexander McQueen and the punk, theatrical pieces of Vivienne Westwood. He sketched looks from the runway shows of labels like Baby Phat, which featured thin silhouettes, short skirts, and small corset tops alongside big shirts and pants. “It was the sick proportions, it was the attitude of the person walking, that just felt so confident,” he said. “I was never that confident. So that attracted me — I want to feel that way or make people feel that way.” He uploaded his sketches to DeviantArt, a pre-Instagram platform where artists could comment on each other’s work. Rogers saved eye-pleasing color-field art, scans of comic books, and images of the eccentric magazine editor Isabella Blow. “LiveJournal, DeviantArt, and Tumblr were formative for me to figure out what my voice was, what people responded to, how I could create community,” he said. “Which I needed to survive and not be bored to death.”

Growing up in Baton Rouge, Rogers was taught that he always had to look “nice” — presentable, put-together — “especially as a Black person, you couldn’t give anyone a reason to say anything,” he said. One of the most polished dressers he knew was his grandmother, who passed away the summer before he started sixth grade. “She was always monochromatic: It was a green jacket, green shoe, green bag. Red jacket, red shirt, red shoe.” But Rogers was resistant. When dressing for church, he tried to slightly disrupt expectations; he would wear a lime-green tie with an olive-green shirt under his suit blazer. These ensembles constituted some of his earliest experiments with color. “I implement that sort of color theory in the work that I do now,” Rogers said. “I like mixing shades of the same color in a look that wouldn’t necessarily go together.”

After Rogers graduated from high school, he went to the Savannah College of Art and Design. There, he liked to dress with flair, wearing necklaces made of rubber bands that the lunch ladies loved. He completed the assignments the way professors wanted, his friend and classmate Sahiba Johar said, like when he sewed a traditional button-down shirt, then made one for himself that was embellished with an oversize collar. (“He would say, ‘Thank you for the feedback,’ and then go on to do whatever he wanted,” Dean Sidaway, his former professor, said, laughing.)

Still, “the entire time, I felt like there were lots of people who didn’t get what I was doing,” Rogers said. He thought he would be taken more seriously if he made clothes in the vein of 1990s anti-fashion, luxury minimalist wear that conveyed seriousness, thoughtfulness, and intelligence and, in the eyes of some, seemed in better taste. Sidaway remembers the first designs he saw from Rogers: 1950s silhouettes, little waists and full skirts, in “exuberant colors.” One professor told Rogers his work was tacky and dated. And as someone who was Black and queer, it was assumed, he said, that “obviously you don’t have taste.” But other professors encouraged him to trust his instincts. Rogers said he used to constantly ask one teacher what he thought of his designs: “He said, ‘Stop asking me. You know what you like, and you know what you want to see.’ ”

Rogers liked bright hues and head-to-toe color looks because of what he saw growing up, but he was attracted to visual tension — irregularities like mixed prints that suggested a chaos opposite of the polyester-satin suits he saw in church. He was bored when he had to use charcoal and pencil in art class. “Color as object is really important to me,” Rogers said. “ ’Cause I never really needed to represent anything; I just wanted to make people feel something.” I asked him what he wanted them to feel. “Maybe special?” he said.

Rogers believed there would be people who eventually understood his clothes. “I was like, There’s gotta be somebody who gets it,” he said. “My parents instilled in me that I could do it — they were like, ‘Look at what has happened before you and study.’ ” In high school, he read books about how to tailor with horsehair and chest padding and hand-stitch with twill tape. He interviewed himself in the shower, drilling himself on questions that journalists would eventually ask about what he stood for and why he made clothes. As a queer boy who came out in middle school, he had felt like he needed to recede and hide, even though he wanted to stand out. And as a design-school student in the 2010s, he assumed he’d spend his life making more stereotypically respectable fashion — understated, tailored basics. “I didn’t think I was going to be making cartoon clothes. I feel like I’m making clothes for cartoon characters, in a way. If someone wears something of mine, a kid could draw it,” he said. “It’s veering on tacky, it’s veering on distasteful, it’s veering on garish. I’m doing all the things that I was told I couldn’t do.”

After graduating from SCAD in 2016, Rogers moved to Brooklyn and started waiting tables. “I couldn’t find a job because nobody wanted to hire me,” he said. “My stuff was too colorful, and it wasn’t going to fit.” But at the beginning of 2017, he started working as a designer at Diane von Furstenberg, a house known for embracing prints and color. Those early days, Rogers recalled, felt like an action movie. He was working at DVF full time and sewing his own clothes in his kitchen with his friends, and now–business partners, David Rivera and Alexandra Tyson, throwing together photo shoots to post online. He messaged stylists on LinkedIn and sent samples when they responded and built an Instagram following posting his sketches, inspirations, and references.

Rogers had created a collection with an emphasis on tailoring and “acidic femininity” for his senior thesis at SCAD, and not long after he released it, a former classmate DM’d him: She was working for the stylist of the rapper Eve and requested pieces for a talk-show appearance. Rogers dragged six garment bags onto the train to Harlem, his arms numb by the time he reached the apartment. Cardi B was his next client; she wore his fox, minx, and ostrich mosaic coat with splashes of pink, green, and orange to the 2017 BET Awards. He got thousands of new Instagram followers that day, but the exposure was not translating to sales or to being stocked; he and his collaborators were still making clothes by hand, and they had other jobs. He would cold-email editors asking if they wanted to look at his clothes and receive no replies.

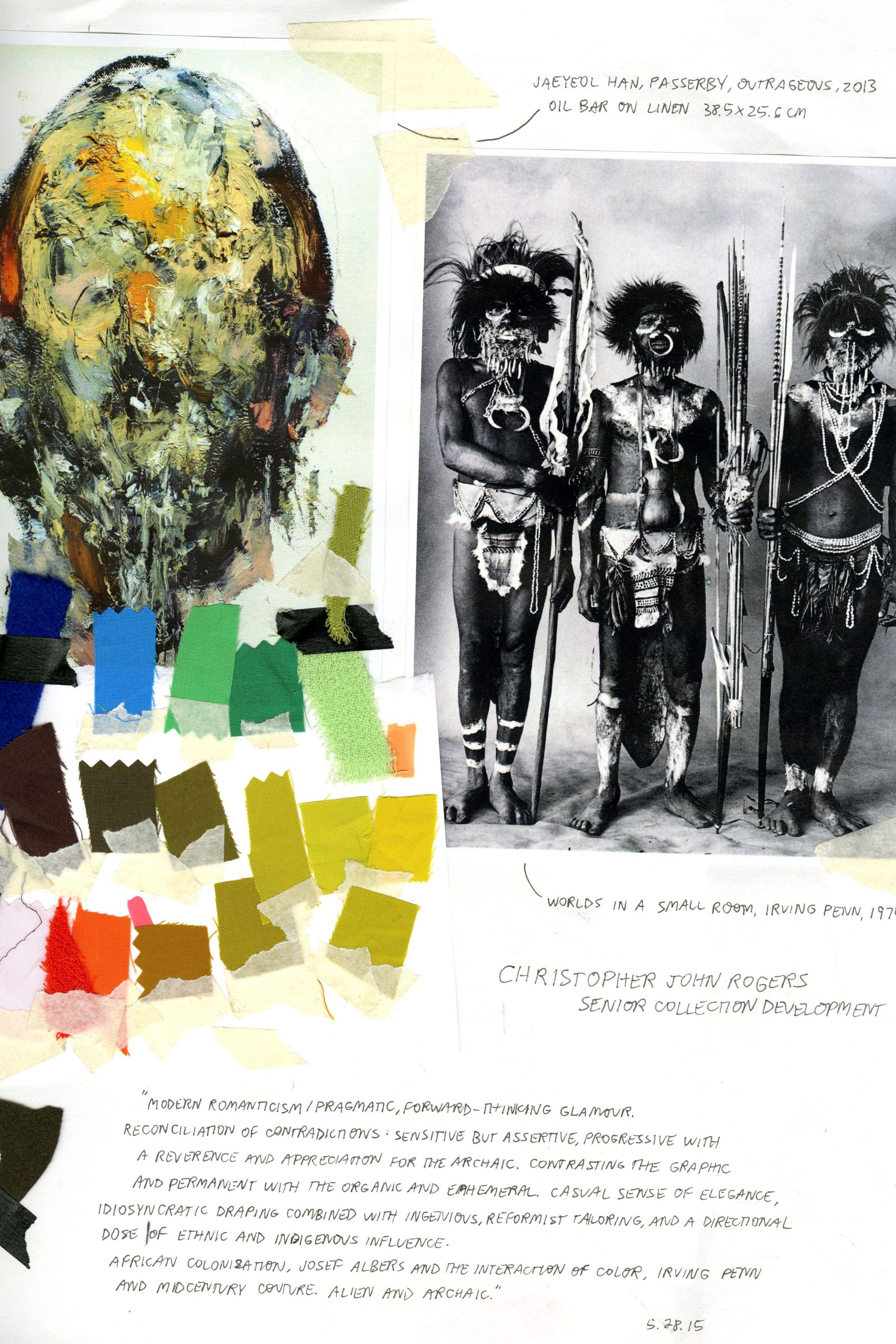

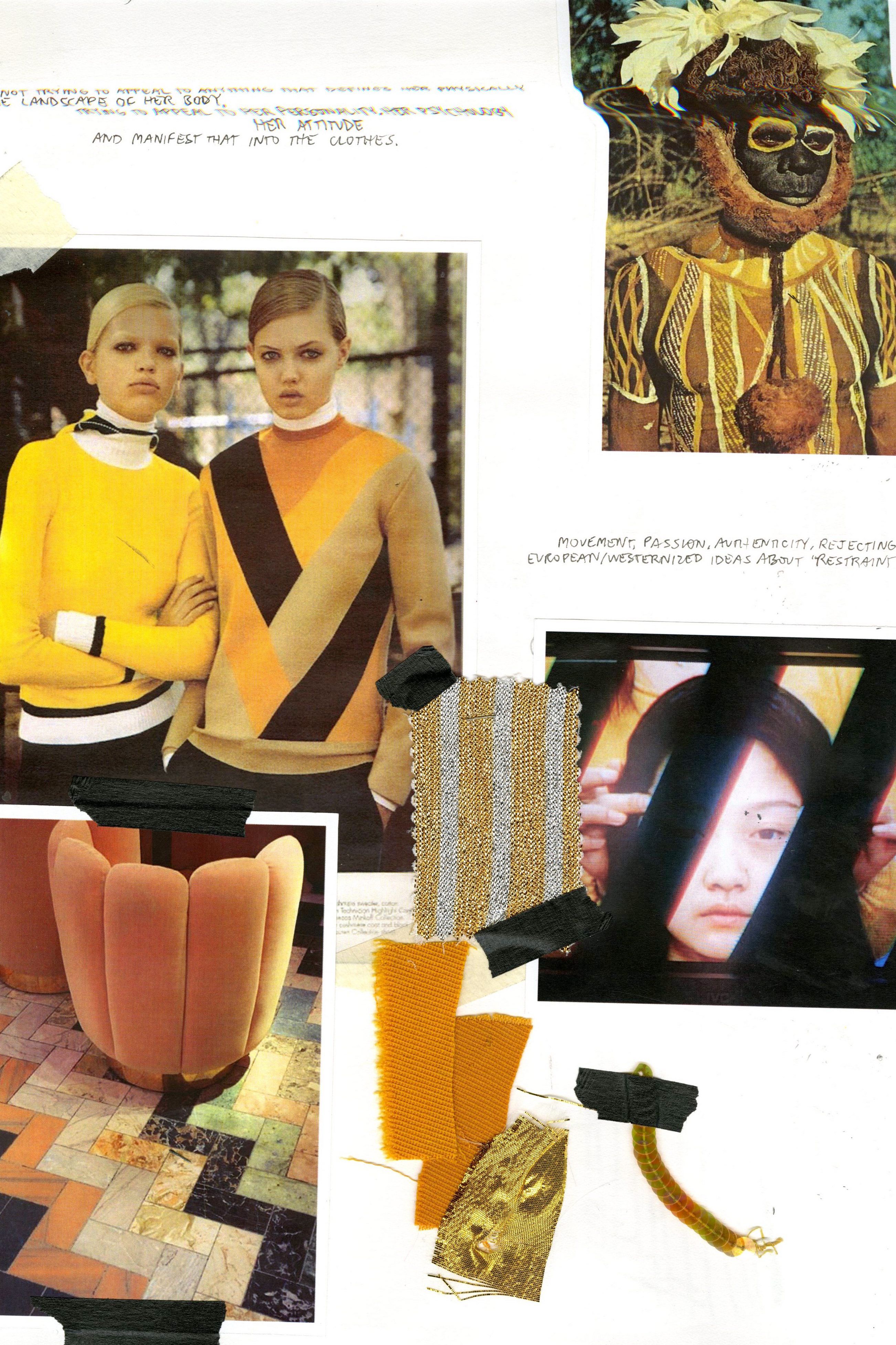

Sketch from Rogers’s junior year of university, 2015.

Process page from his senior-year thesis collection, 2015.

Process page from his senior-year thesis collection, 2015.

Sketches, 2014.

Sketch from Rogers’s junior year of university, 2015.

Process page from his senior-year thesis collection, 2015.

Process page from his senior-year thesis collection, 2015.

Sketches, 2014.

In the fall of 2018, Rogers emailed Ebony L. Haynes, who was then the director of Chinatown’s Martos Gallery (she’s now a senior director at David Zwirner). He was looking for a space to stage his first presentation, and Haynes agreed to talk. “I told her, ‘I don’t know how to say this, but we don’t have any money to pay for it.’ And she said, ‘Why would I ask you to pay for it?’ ” Rogers recalled. “Black women have always looked out for me in this industry.” His former classmate and current brand director Christina Ripley produced the presentation in two days. Rogers’s hustle worked. The CFDA attended, and afterward, buyers from Net-a-Porter, Barneys, Browns, and Harrods came to view the collection in person. Early clients were most interested in his eveningwear, the color and volume of which, after the dominance of athleisure and streetwear in the 2010s, were “starting to come back into fashion, which gave me an advantage because it was a natural inclination that I had,” Rogers said. “I was kind of salty because I wanted to be the girl to bring it back.”

Rogers staged his second presentation on a snowy evening in early 2019 in an abandoned, unheated space on Canal Street (“We had no coins,” Rogers said). The models, standing on Styrofoam pedestals, wore a fluffy, floor-length yellow dress with sleeves and a skirt made of tulle-filled layers; a tiny strapless minidress in shades of green; a blood-red tailored suit; a collared shirt with ruffly cuffs that ballooned out and wide-leg pants, both in pink and purple stripes; a lilac button-down shirt with exaggerated sleeves and a matching long, pleated skirt; and other confetti-hued concoctions. The space was crowded with friends, fashion writers, and designers, and the line to get in went out of the door. The night was euphoric. Two months later, Rogers was fired from Diane von Furstenberg. (Von Furstenberg said she wanted him to pursue his own designs and maintains that he wasn’t fired.) “Up until then, what I was doing wasn’t deemed a conflict of interest. Then it became a thing,” Rogers said. “Even though I wasn’t selling clothes at the time — we didn’t have any orders or anything — it was still kind of like, ‘You’re making a name for yourself, and you need to not be here.’ That really was like, ‘Oooh, the girls are a little shook.’ ”

Rogers had no savings or real employees, but he needed to build a business. That September, he staged his first runway show, and Net-a-Porter finally placed an order. In November, he won the CFDA/Vogue Fashion Fund, which gave him $400,000. Rogers used the Fashion Fund money to hire his team and a financial adviser. Soon he was everywhere. Rihanna wore his wiggle-ruched stretched-velvet dress in electric orange, and Michelle Obama’s stylist requested a custom look for the First Lady. The designer created a metallic trouser suit with Swarovski crystal buttons. “There’s a scale to the work that I do,” Rogers said. “The vocabulary is really big. So if someone wants a simple tailored suit, we make sure that the color is really vibrant or there’s something with the fabric. With Michelle, the color wasn’t super-crazy — it was just cyan — but it was iridescent.” For her inauguration in 2021, Vice-President Kamala Harris wore his shift dress and matching overcoat in a blue violet that changed with the light.

A few days into the New Year, Rogers and Ripley virtually walked a team of buyers from Bergdorf Goodman through his pre-fall 2022 collection. When he began designing it, he was motivated by joy and southern propriety, clothes looking polished and pulled-together. And then he “fucked it up.” The effect was dazzling: a ruffled blouse and structured suit in acid yellow; a strawberry-shaped gown in gray metallic cotton; a skinny black knit dress with a free-fall V-neck lined in orange, yellow, and green. There was Lurex and weird, clean draping. A skirt with asymmetrical poofs on either side had been inspired by crumpled paper balls and carryout bags.

It was the third of his market appointments that day. Rogers and Ripley had organized the clothes from the collection in a rainbowlike enclosure facing a high table with a laptop. As they talked through the offerings, Ripley pulled pieces and handed them to Rogers to show the buyers. They seemed enraptured, alternatively commenting “Love!” and “Those are amazing” with each garment. “Our holiday exclusive has been another highlight. We’ve already sold 152 units,” one buyer said.

Rogers held up a trench in hot pink. A buyer asked if it was the same as one Rogers made in acid green. “It’s the same, except the pink is nylon, so it’s much more crisp, a little bit more noisy,” Rogers said.

“Seen and heard,” the buyer said.

Rogers laughed. “Exactly.”

Rogers’s typical customer is a professional over the age of 35, and his fan base includes gender-nonconforming people who buy his suits and shirt dresses, which often button on the men’s side. In Rogers’s mind, the “CJR squirrel” (what his team calls their most representative customer) wears clothing not as armor but as a way to be seen — like, “I feel so amazing and want other people to notice how good I feel,” he said. He told me about a rancher who buys his clothes every season: “So she has all these cows, but she gets dressed up and goes to town to run errands. And people make fun of her, like, ‘Who’s this woman?’ ” he said. “But she flies to Bergdorf Goodman every so often to shop, and she loves my shirtdresses.” Later, when I visited the CJR racks at Bergdorf, I saw an older white woman with a Prada handbag take the same shirt Ripley was wearing at the market appointment to try on. She told me she lived in the Bahamas, and a store manager said Rogers’s name was “now international.”

After the Bergdorf meeting, I asked Rogers how it felt to be a current darling of the industry. It had happened at a moment when fashion’s players were ready to reembrace maximalist ideas; Rogers had been part of the reason for that shift. “It’s kind of scary,” he said. “It’s really cool, but I know it’s so transient. I want to not think about it and find excitement in actually making the clothes and seeing people happy in them.” In November, when Rogers won the CFDA American Womenswear Designer of the Year Award over more established designers like Gabriela Hearst and Marc Jacobs, he felt “verklempt,” but a part of him wondered about the politics of it. “I didn’t know what to think,” Rogers said. “Is my win indicative of a need to seem relevant, or fresh, or modern? Or is it merit? I mean, obviously I know it’s merit, or should be. But is it an optics thing? Which is a really sad thing to have to say.” He kept thinking about the question as Emily Blunt, who was wearing his lean tangerine suit that night, and Zendaya, who wore his grape-and-black tulip-skirted dress with a deep neckline and wide obi belt to the 2020 Emmys, congratulated him.

For all the fantasy of his clothing, “there is a certain straightforwardness to the work that I do,” Rogers said, “that I don’t think people always get unless you see the clothes in person or unless you wear them.” He worries about whether consumers can see beyond his experiments with color and shape and appreciate the craft of the clothes, not just their novelty. “Do people really get what I’m doing? Or do people just see it and respond to it? Sometimes I think people are only reacting to it flatly,” he said. “There’s a lot of intention that I put into the work.” He thinks deeply about construction, and details, and proportion, and fit — things that can go unnoticed if the color and fabric are what draw attention. Like his wool jacket in a 1990s men’s shape with slanted welt pockets that match the lapel and that, rare for womenswear, has interior pockets. It’s considered, even if it is the color of green M&M’s. He deliberately cuts his clothes to accommodate more bodies. Nearly all of his shirtdresses have invisible zippers — “So you can show more leg if you want, or have access to your pocket if you’re wearing pants under the dress,” he said — and many of the wide-leg trousers have lower rises.

In February, a few weeks after the meeting with Bergdorf, he had a mini-breakdown from the pressure he was starting to feel from his team and the industry. He wanted to listen to his own voice when it came to growing his business. He didn’t want to partner with investors yet, but instead focus on the sales from clothing and, potentially, new products. He took out his phone and deleted Instagram and an astrology app. (“I need to not look at anything,” he said.) After his fall 2020 collection, he has been taking a break from putting on shows, which are costly and time-consuming, concentrating instead on look books and e-commerce — something many young designers have been doing to create more thoughtfully outside the frenetic season schedule. Some wonder if Rogers’s next step might be to lead womenswear design at a European couture house, as Virgil Abloh did for menswear at Louis Vuitton. (When I asked him if he has a dream house, he laughed. “Yeah, but I’m not gonna say.”)

“Recently, I’ve been struggling with this idea of hype and permanence,” Rogers said. “There are people I have to think about other than myself — I have to think about the people that I employ, the customers who rely us on to now fill some niche void in the fashion landscape.” I thought of his newest collection, and of a white linen suit with Easter-egg-colored pinstripes that I had wanted to try on. It reminded me of his oversize lilac suit with pants that swished, and it didn’t look like anything else on the market. Rogers wants to expand the brand’s look, make clothes that communicate his vision, “without having to yell.” He is taking a break from ballgowns and toying with the idea of an all-black collection. “I’m still trying to make the clothes that little me would have been excited to see,” he said.