In late June, while public-school students across the city were attending their graduation or “step-up” ceremonies over Zoom, the NYC Department of Education, as part of its planning for school reopening in the fall, asked every principal in the system to measure their buildings. Armed with floor plans and laser pointers, the principals visited each classroom, noted which ones had windows, and figured out if any other spaces could be converted into classrooms. Then, after dividing the total space by the number of students, they were expected to come up with a reopening plan that would meet social-distancing guidelines — all in less than a month.

To Medi Ford, a high-school teacher in Brooklyn, this seemed crazy. Her principal was smart, creative, and a former science teacher, but she was not a public-health specialist or an epidemiologist. Ford had been in the public-school system long enough to know that there were many principals who would not be up to the challenge. “The DOE just said, ‘Good luck to your school. I hope you figure it out,’ ” Ford told me. “To me, that’s a recipe for chaos.”

Ford’s school is located on the top floors of a former torpedo factory near the Dumbo waterfront. After her principal completed the mandated walk-through, Ford visited the school with her own tape measure. She had been in the building only once since March, when the city’s schools had shut down in a whirl of panic and confusion, and she found the experience eerie. She was required to get permission to enter two days in advance and to sign in at the door with a school-safety officer.

Inside, the school was dark and empty. Ford walked through the halls and found that they were less than eight feet wide. The hallways had always belonged to the students: It was where they could escape the confines of the classroom. She took a video of the sink in the hallway that had been out of commission ever since lead was discovered in the water. Fearing cockroaches, she decided to skip the bathrooms and the gym. Entering her classroom, she found it almost exactly as she had left it months ago, a pre-pandemic time capsule. Now, in the era of social distancing, she realized it was far too small for her 20 students. Measuring the tables at which her kids once sat, working in groups, Ford found that they were less than six feet long, meaning they could now accommodate only one student at a time.

“It was sad,” she says. It was sad to see her classroom, set up for lively group discussions, rendered unusable. It was sad to imagine her students having to cling to the edges of the hallway as they pass one another. But Ford was also angry. A lot of time had passed since March, and almost nothing had been done to prepare the school to reopen. It seemed unthinkable that it could now be done in time.

As schools struggle to reopen under conditions of a still-festering pandemic, New York City faces a cruel paradox. Because the virus came here early and did unspeakable damage, and because the city endured a three-month lockdown, New York is now, from a coronavirus perspective, one of the safest urban school districts in the United States. It is therefore theoretically one of the easiest to reopen. But for the very same reasons, it is the hardest school district to reopen. Its employees have seen what the virus can do to entire communities. Its finances have been decimated. Many teachers, like the families of their students, have fled the city for safer ground.

Worst of all, the people charged with preparing the most ambitious school reopening in the country are angry at one another, working at cross-purposes, and full of distrust. Teachers feel they are being asked to jeopardize their very lives to provide an inferior educational experience so that other adults can go off to work. School administrators and staff feel they are being asked to plan the impossible with too little time and too little money. Working parents, especially mothers, find themselves shunted back into the home, sitting alongside their children for hours as they Zoom in to their classes. And looming over all the confusion and divisiveness is a touchy, querulous, voluble mayor who cannot seem to make up his mind. Nearly everything has conspired to prevent the city’s schools from reopening at anything close to their full capacity, if they reopen at all.

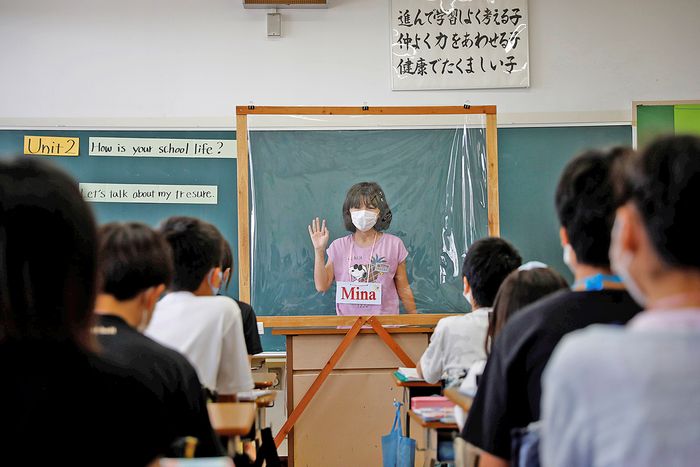

Teaching is not like any other profession. You aren’t sitting at an isolated computer, or driving a vehicle, or hammering nails on a construction site, surrounded by adults who can reasonably be expected to wear masks and observe social distancing. You’re in an enclosed space all day, surrounded by kids. You teach them to tie their shoes, open a bag of potato chips; you teach them how to read, how to tell time, what an isosceles triangle is, what caused the Civil War. No one besides their parents can make more of a difference in their lives. Teachers are underpaid, overworked, often overlooked — and, universally, profoundly trusted and beloved.

According to Michael Mulgrew, a former high-school English teacher from Staten Island and now head of the powerful United Federation of Teachers, the union started planning for the fall in the first weeks of April. Mulgrew says the planning committee looked at all sorts of options: “Any plan you can think of, we discussed.” The committee’s members looked at outdoor learning but concluded that, by the end of October, the weather would be too cold and wet. They explored keeping high-school students at home and letting elementary students spread out into the high schools but could not solve the staffing problem. “A teacher is not just a teacher,” Mulgrew says. “An elementary-school teacher is a specialist in child development. A high-school teacher is a specialist in communicating complex concepts. You can’t just put a high-school teacher in a class full of kindergartners.” In the end, they came back to alternating kids between classroom and remote learning to create enough space for social distancing. “Anyone who does the numbers would see: Either you triple the number of classrooms and teachers or you go hybrid,” Mulgrew says. “It’s just math. Once you start with the safety piece, it becomes a space and teacher-capacity issue.”

Many other school districts across the country were coming to the same conclusion. But in New York, there was a difference: The teachers and the mayor were not speaking to each other.

Mulgrew says the mutual animosity goes back to the winter. In January, a teacher returning from a trip to China was put in quarantine. The following month, after February break, teachers and students returning from field trips to Northern Italy discovered that tests for the virus were almost impossible to come by. “The mayor was out there saying everyone should get tested, but they couldn’t get tested,” Mulgrew says. Then, in early March, a high-school teacher at Grace Dodge in the Bronx tested positive for the coronavirus — but the DOE refused to close the school, because the teacher had faxed in his test results himself rather than having the hospital do it. “That’s when things got super-ugly,” Mulgrew says.

On March 12, at a meeting with parents and advocates, Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza was asked about a petition signed by 108,000 people asking the schools to shut down. Carranza replied, flippantly, that when he got a letter from 108,000 epidemiologists, then he would close the schools.

The next morning, Mulgrew had a contentious meeting with Mayor de Blasio. He urged the mayor to close the schools, but de Blasio resisted. “Then he did that press conference,” Mulgrew says. De Blasio brandished a letter from a big health-care-workers union arguing that schools needed to stay open so its members could take care of the sick. “Which is rich,” Mulgrew says, “because by Sunday, that same union was saying they didn’t support that position.”

That morning, Mulgrew announced that he would be taking the city to court to close the schools. By the afternoon, the governor and then the mayor announced the schools would be closing.

Since then, Mulgrew and the mayor have spoken only once, on a conference call of the city’s school-reopening commission.

I ask if that’s abnormal, for the mayor not to be talking with the head of the teachers union, especially at a time like this.

Mulgrew agrees. “It’s strange,” he says.

When the DOE finally issued its preliminary guidance on reopening, in early June, its “space-utilization analysis” suggested that a “full size” classroom of about 800 square feet could hold nine to 12 students. By the DOE’s estimate, that meant most schools would have to divide their student body into two cohorts — one cohort would attend school in person on alternating days or weeks, while the other engaged in “remote learning” at home. The plan devoted an entire page to laying out various possible schedules for the cohorts without addressing more fundamental questions — how, for example, teachers could be expected to juggle both the in-class and remote-learning cohorts simultaneously.

Worse, from the parental perspective, limiting in-person classes to 12 students would mean that a fairly typical New York City classroom of 30 kids would have to be split into three cohorts, not two. The principal of P.S. 107, a popular school in Park Slope that appears in Mo Willems’s book Knuffle Bunny Too, sent a letter to parents after doing the DOE-mandated walk-through of her building and measuring the classrooms. Absent some kind of intervention, she told parents, their kids would be attending the school in three cohorts this fall. That meant there would be weeks when students would have only one day of school. And what if that day fell on, say, Yom Kippur? For many parents, the city’s plans — rolled out slowly and semi-publicly at a time when they were still stuck at home all day with their kids, wrestling with Zoom classes — were a real blow: The pandemic was not over, and it wouldn’t be over come fall, and there was no telling when it would be over.

I should admit at this point that I was not a neutral observer of these events. My older son was just finishing up pre-K, over Zoom, and headed for kindergarten. When I read about the letter, I looked at my son’s school, which was at full capacity, and shuddered at the prospect of a one-in-three school year. In mid-June, our son’s pre-K teacher sent parents a DOE survey to gauge our preferences for school reopening. It asked us to rate, among other things, how important it was for us that the school be cleaned on a regular basis. The science on surface transmission of the virus was still evolving. Were they asking us for our understanding of the latest studies? The survey did not inspire confidence.

But there was also, finally, a clear outline of possible schedules. Parents were asked whether we would rather have our kids attend school every other day, every other week, or online only. I took that last option to be an ominous warning. With the other dads in the park, I gamed out the possibilities. It was possible that after all these months of lockdown, we were still not going to have any school in the fall.

There was another way to look at the online-only option. In July, I spoke with the mother of one of my son’s pre-K classmates, an interior designer named Marian Akinloye Ennis. Her husband works in the lumber department at Home Depot. The couple lives in Bed-Stuy, and they have four girls, ages 10, 8, 5, and 1. Ennis says that, thankfully, orders at the design firm where she works have not slowed during the pandemic; the clientele is so wealthy that they have not been affected. But her own life has changed a great deal. She has stopped going into the office, locking herself in her bedroom for entire days when she needs to get work done, leaving her husband or a babysitter to watch the girls. She and her husband have put in hundreds of hours to transform their backyard, previously nothing more than a pile of dirt, into a garden with raised beds. They’ve done this for their daughters, whom they, out of an abundance of caution, had not let out of the house since the pandemic began.

Ennis is from Texas, and though she has been in New York for over a decade, she still talks with a slight drawl. She acknowledges how much it would help to be able to drop the kids off at school this fall. “It would be nice to have them out of my hair and have the house to myself,” she says. “I wouldn’t have to lock myself in my room as much.” She’s worried about her daughters bringing the virus home, but she’s more worried about others, and the effect it would have on her girls if they made someone sick. “You just hear these horror stories about what happens to the adults in the kids’ lives,” she says. “How horrible would it be for them to lose a teacher because we decided that this was the best thing to do?”

She told me she wants to know all the details: what the schools plan to do in response to various eventualities, how confident they are in their ability to keep everyone safe. Then she says something I had not heard from many parents.

“In a life-and-death situation,” she says, “what do you do?

As school administrators and teachers and parents struggled to answer that question, the science was constantly changing. There was disagreement among scientists about how the virus was transmitted and the role children played in transmission. From the very start, in Wuhan, observers were surprised and relieved that children did not seem to be among the ones afflicted by COVID. But there was no clear explanation for why. In a study that received extensive coverage in the New York Times, the eminent German virologist Christian Drosten found that “viral load” does not vary by age. “Based on these results,” he wrote, “we have to caution against an unlimited reopening of schools and kindergartens in the present situation. Children may be as infectious as adults.”

In real-world settings, though, kids did not seem to be making other people sick. An early contact-tracing study from Singapore that looked at confirmed COVID cases in three schools found no evidence that children, especially small children, transmitted the virus at all. More recently, a large South Korean contact-tracing study found that kids under 10 transmitted the virus at a significantly lower rate than older kids and adults. But the rate was not zero. Some of these studies received attention in the news media; others did not. In a way, it didn’t matter. In the absence of a definitive explanation for why children did not appear to transmit the virus, the science could not be said to be conclusive. And the parents and teachers I spoke with were not necessarily monitoring the latest studies. They were simply reading the news. A summer-school teacher had died in Arizona, they told me. There was a COVID outbreak in day-care centers in Texas. A little girl in Florida had died.

There was debate around the developmental effects of continued school closure on children, especially those from poorer families with less access to educational resources outside school. Some researchers compared the likely effects to the “summer slide,” when kids spend a bunch of time playing with worms and forget what they learned at school. But as Megan Kuhfeld, a senior research scientist at the assessment nonprofit NWEA, explained to me, the analogy is misleading. The summer slide does not increase inequality, because both poor kids and rich kids play with worms. Whereas during the lockdown, wealthier Zip Codes produced many more Google searches for educational topics like Khan Academy than did poorer Zip Codes. A continued shutdown of schools, Kuhfeld believes, would most likely increase inequality, and the longer it lasts, the more it will do so. She says the covid shutdown is more comparable to a political or natural cataclysm: the massive school closings in the South in the late 1950s as a protest against desegregation, the 1968 teacher strike over community control of New York City schools, Hurricane Katrina. In each case, there was significant short-term learning loss, usually accompanied by longer-term effects as well.

One of the most insistent and authoritative voices arguing for school reopening has been that of Dimitri Christakis, the head of the Center for Child Health, Behavior, and Development at Seattle Children’s Research Institute and editor-in-chief of JAMA Pediatrics. In May, Christakis published an editorial urging policy-makers to start thinking about school reopening. Most people, he believes, don’t realize how long it will take to develop a vaccine and how harmful it would be to keep schools closed until then. “The earliest prognosis for a vaccine is not until early 2021, and even then kids won’t be, or shouldn’t be, the first group to receive them,” he says. “So we’re talking about a period of a year, possibly two years, before it’s completely safe for kids to go back to school. That is an unconscionable period of time to keep kids out of school.”

Christakis is a leading expert on the baleful effects of screen time on young minds. Now, with children drowning in an unprecedented stream of screen time, he worries about increased depression and anxiety among kids of all ages. He points out that kids who fall behind in reading by third grade are less likely to finish high school. And he blasts federal health officials for what he calls impractical guidance.

“Think of what the CDC is,” he says. “They’re the center for disease control. I don’t know who put together their guidelines, but my guess is they weren’t child-development experts. They certainly weren’t teachers.” The entire debate, he says, is being dominated by infectious-disease experts. “If you ask them, ‘Can schools play an important role in the transmission of the virus?,’ the answer is, ‘Yes, they could!’ But they’re not thinking about the risks of not opening schools. Our children have already paid a heavy price, and they’re going to pay a heavier price if we keep them out.”

Christakis acknowledges that a small number of kids have gotten sick from the virus, but he says this is rarer than being hit by lightning. He understands why teachers are afraid of going back into classrooms, but he insists that such fears are not rational. If they take the necessary precautions, he says, their risk will be very low, almost nonexistent. He compares teachers to health-care workers: When doctors and nurses have the proper equipment and follow the protocols, they do not get sick from COVID.

Christakis and I spoke on the morning of July 7. I found it comforting: Here was a person with data, a respected pediatrician and epidemiologist. And he was telling me that it was okay for my child to go back to school, that it was okay for all our children to go back to school. He conjured a vision of schools that could be as safe and clean as hospitals, where children play with one another and develop their natural capacities, overseen by kindly teachers in N95 masks.

Was it possible, I thought, that the burbling anxiety coming from teachers and parents was just a natural reaction to the idea of subjecting themselves and their children to any risk, however slight? The spread of COVID in public schools can never be reduced to zero. But what if it could be reduced to the same level as in the general population? What if going to school were no riskier than shopping for groceries? Shouldn’t parents who have enjoyed the luxury of working from home in total bubbles be prepared to accept the same level of risk as those who continue to stock warehouses and deliver packages and drive cabs? Shouldn’t teachers, who signed up for a career in public service, be prepared to fulfill their obligations like other essential workers — the workers, in fact, who make virtually all other work possible?

But risk is separate from perceived risk. And perceived risk is closely bound up with one’s view of the people who are telling you that your risk is low.

The day after I spoke with Christakis, de Blasio and Carranza appeared together to officially announce their plan for a partial school reopening. The mayor said it would be the “greatest school year in New York City history.” Students could opt to go online-only for any reason; teachers and staff could request a medical exemption to work remotely. The schools, Carranza added, would be deep cleaned each night. And their HVAC systems would be upgraded.

I didn’t know what an HVAC system was, but it sounded good. And so did cleaning. Then I called Robert Troeller, president of Local 891 of the International Union of Operating Engineers. Troeller’s 800 members, technically called “custodian engineers,” are the keepers of the 1,400 buildings in the public-school system. They are responsible for every roof, window, sink, water fountain, toilet bowl, cafeteria floor, and stairwell. The current level of upkeep requires an annual budget of $640 million just for staffing — not accounting for all the additional labor and supplies that will be needed for any COVID-related cleaning.

Troeller, himself a former custodial engineer, says the DOE’s cleaning protocols are unrealistic. “They are promising the teachers union and the teachers that they are going to have more of a presence of custodial workers to continually provide janitorial services during the day and do what they call a ‘deep cleaning’ at night,” he says. “To be honest with you, I don’t know what they mean when they say ‘deep cleaning.’ ”

Before COVID, Troeller says, deep cleaning referred to what happened during the summer, when entire buildings were scrubbed and painted and waxed from wall to wall. “That’s certainly not happening overnight,” he says. “I think what they’re talking about is that each horizontal surface will be wiped down and cleaned and sanitized. The problem is that the budget we received on July 1 is the same budget that we received last year. They want all these additional surfaces cleaned; they want to have more custodial presence during the day and more cleaning at night. Well — who’s doing it? Where are the bodies going to come from?”

Troeller says his custodians will do their best, as they have been doing since March. They were at the schools throughout the shutdown, as the buildings were transformed into regional enrichment centers and food-distribution depots. They were there through the darkest days of the curfew, when Troeller urged his members to keep their DOE letters always on their person. They were essential workers. The custodians never left.

Troeller warns that parents should not expect schools to look as clean as they usually do. “People don’t understand that cleaning and sanitizing are two different things,” he says. “The more time you spend sanitizing, the less time you have to sweep and mop.” The decals that schools plan to put along hallways and stairwells to help with social distancing will make it harder to buff and shine the floors. But that won’t mean the school isn’t being cleaned where it needs to be.

“Parents and teachers are going to expect the place to look cleaner, but it will look dirtier,” Troeller says. “But it will actually be more sanitized.”

Carranza’s promise, meanwhile, that every school will receive an update of its HVAC air-filtration system strikes custodians and teachers as a bad joke. Medi Ford has been trying to get her school to replace the tables in her classroom for the past year, without success. “If I can’t get money for desks,” she says, “how the fuck are they going to get hvac right?” In fact, Troeller says, most schools were built so long ago that they do not even have hvac systems. Installing one now would be “a monumental cost. There’s no realistic way to add it. Forget about cost — it would be a giant capital project.”

In most schools, Troeller says, the most effective air-filtration system is going to consist of opening the windows.

In late July, about a month after the school walk-throughs, principals across the city held a series of all-school Zooms with parents to deliver the bad news: Students would be in school only one day in two or, in some cases, one day in three. One elementary school in Brooklyn told parents that the “day” would go from 8 a.m. to 11:20 a.m. Some high schools expressed their desire to go all remote.

On July 21, I attended the virtual meeting for my child’s elementary school. The assistant principal told us they had measured the school, counted the students, and come to the conclusion that they could accommodate half the student body at any given time. I felt a surge of relief: At least we had avoided the dreaded one in three. The school planned to go two days in person, then three days virtual. Now they were in the process of physically preparing the school, removing carpets and any extra furniture and leaving only the hard, cleanable exteriors of floors, desks, and plastic chairs.

But that, in a way, was the easy part. The assistant principal said 21 percent of parents at our school had indicated on the DOE survey that they wanted to go fully remote. The question of who exactly would be teaching those students was still up in the air, given that teachers at our school would be busy with the in-classroom cohorts.

A parent asked when the details would be available. The assistant principal said she did not know. “I hope it’s by August 7,” she said — the deadline for parents to select the online-only option.

The assistant principal, who used to teach math at the school, then went through a remarkable list of other things they still had not figured out. To keep the exits and entrances from turning into social-distancing catastrophes, the school would have to open more of its doors, but there were only two school-safety officers and no more forthcoming. If the state of the science come September was that everyone needed their temperature checked before entering the building, and there was only one school nurse but many school entrances, who would do the checking? And what if a kid had run to school, or ridden his bike, and his temperature was temporarily elevated — who would make the determination about that?

And on and on. To keep the bathrooms from having too many kids in them at any one time, someone would have to be posted outside — but who? And what about lunch? Teachers are contractually, and psychologically, obligated to leave the classroom for the lunch period and have some time to themselves. In which case, who would sit with the kids during lunch? Who would take out the trash from lunch? What about substitute teachers — did we want to invite a stranger, basically, to be with our kids, not knowing how careful that person had been about the virus? And what about recess? The DOE had not yet indicated whether recess would be allowed. The same was true for our school’s wonderful after-school program. Would it be okay as long as the kids kept their social distance, or would it interfere with the deep cleaning that was supposed to take place every night?

Once she finished her presentation, while intermittently being climbed on by her 2-year-old, our assistant principal fielded dozens of questions from nervous parents. Marian Akinloye Ennis, the interior designer who had kept her kids at home since March, was impressed by the presentation. The administration seemed to have thought of everything. But there was so much that was still uncertain. There was still so much that none of us knew.

By the last week of July, barely a month before school would traditionally start, the conflict over reopening had reached new heights, spurred on by President Trump. The American Federation of Teachers announced it would support “safety strikes” at its locals if schools were forced to reopen under unsafe conditions. The move was directed at places where pro-Trump governors might try to open schools despite soaring COVID rates. Union leaders did not think things would come to that in New York. After all, COVID transmission was low, and it was possible that schools could open safely. But they also knew that many rank-and-file teachers would be strongly opposed to reentering classrooms this fall if the money necessary to guarantee a safe reopening does not appear.

The DOE defended its plan — “We had to reinvent the largest school system in the country,” says Alison Hirsh, a senior adviser to Carranza — but that didn’t make anyone like it. In the absence of clear leadership, other city officials began coming up with plans of their own to replace or supplement the one offered by the DOE. Brad Lander, a City Council member, proposed taking over rec centers, libraries, and other unused spaces to provide child care for parents on days when school was not in session. Mark Treyger, the chair of the council’s education committee, proposed an ambitious plan to delay reopening and arrange for elementary schools to take over high schools, insisting that the city could issue a “clarion call” for the extra teachers needed to implement the plan. Two days later, Public Advocate Jumaane Williams issued a similar plan.

The city quickly adopted a form of Lander’s day-care proposal, but it refused to consider a delayed reopening or prioritizing elementary-school students. The DOE also evinced little interest in a plan floated in a Daily News op-ed by three Brooklyn elementary-school teachers to increase outdoor learning. It was the obvious answer to the problem of both limited space and an airborne virus. But with the city offering no verbal or logistical support for the idea, it became one more barometer of inequality: Only wealthy schools in Park Slope and the Upper West Side, situated near the vast expanses of Prospect and Central parks, were able to move forward with it. Rich white kids would go outside, explore nature, and not get sick; poor Black and brown kids would stay inside and face the risks.

Some inequalities, ironically, may cut in the other direction. In a push known as “prioritization,” a few districts are arguing that some kids — those with special needs, say, or the children of essential workers — should be allowed to attend school in person more often than other students because their need is greater. And many poor schools are so underenrolled that they have the space to bring back all their students in person, if the DOE and the union will let them give teachers’ aides their own classrooms. “The haves become the have-nots, and vice versa,” one school official told me.

Meanwhile, some of the cracks in the DOE plan were beginning to show. Leaders at Stuyvesant High School, one of the city’s most famous schools, recommended going all remote. The school was sorely overcrowded, and a poll of parents had revealed majority support for an all-online model. The DOE said it would not approve such a move: Parents could opt to go all remote, but a school as a whole could not. But the whole point of delegating so much decision-making to the schools had been to let them decide what was best for their communities. It seemed like a repeat of the city’s stubbornness in March.

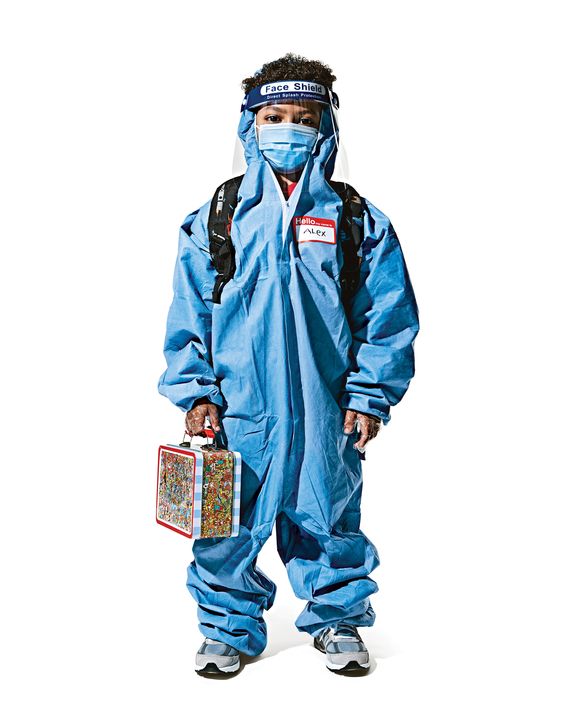

Many teachers worry that the in-classroom experience, as envisioned by the DOE, won’t be very educational. “People think, Yay, school is reopening; it’s going to be like it was, but they don’t understand,” says one elementary-school teacher from Brooklyn. Students will be masked and constantly monitored. It will be less like a school and more like an airport — or worse. “You’re going to have kids who don’t have a mask,” Ford warns. “Either because they forgot it, or their parents couldn’t get one, or they don’t have the information. The school-safety officer is going to show up, and you’re going to have kids treated punitively.”

On July 31, de Blasio announced that schools will reopen only if New York maintains a citywide positivity rate below 3 percent. (It’s currently at one percent.) Officials also revealed that individual schools will be closed for at least two weeks if just two students test positive for the coronavirus — a threshold that many schools are likely to hit. “The essence of this plan is safety for everyone,” the mayor insisted.

But despite the precautions, teachers worry that schools can’t be made safe: The buildings are simply in too much disrepair. “You can’t undo decades of neglect and underfunding in a month,” says Liat Olenick, an author of the op-ed calling for outdoor learning. And many kids and teachers take the subway or the bus to school, which would further expose them to risk.

“I went through cancer,” says Ford. “Do I feel safe going back in the fall? I don’t know. But I don’t trust that it’ll be safe for all of us. There are just too many possible interactions — too many possible ways each person will be exposed to these particles.”

Annie Tan, a fifth-grade special-ed teacher in Sunset Park, shares the same fear. “I want to be back in school when it’s safe,” she says. “But I also don’t want kids to feel in a year’s time that their presence killed someone. I honestly think that’s going to happen.”

An activist union caucus called Movement of Rank and File Educators has floated the possibility of rolling sick-outs in September to protest the push to reopen schools. But most teachers aren’t members of more. One pre-K teacher I spoke with says she is not enthusiastic about going back to school, even though her principal has agreed to let her hold class outside. She feels it will be unsafe. “If someone sent me an invite for a birthday party right now with nine kids, I would say, ‘No, thanks!’ ” But she is going to show up for school. Her husband is out of work, and she can’t afford to go on leave and lose her salary. “I have to do what I have to do,” she says. “It’s like coming back after the six-week maternity leave you get from the DOE. You know it’s not right, but you have to do it.”

One morning in late July, I traveled to Gravesend to meet with a principal named Barbara Tremblay. She grew up in Queens, dropped out of community college, and signed on to become a teacher’s aide, like her mother. She liked the work and eventually got a degree and then another, and became a special-ed teacher and then an assistant principal. She now heads up P.S. 721K, a special-ed high school.

As we walked through the school, she showed me the supply kits she’s putting together for students to use during remote learning: crayons, scissors, glue. Also “communication devices,” she says. I assumed this meant iPads, and in some cases it does. But she also showed me a big red plastic button with a cord attached. People who have use of their limbs, as well as some understanding of cause and effect, can use the button to play simple messages. Not all of Tremblay’s students would be able to use it. But some were doing very well with it.

With evident pride, Tremblay showed me the school’s culinary classroom and the student-run café. She showed me the outdoor space, which she looks forward to using, in the shadow of a spur from the elevated subway. She described the basic logistics: 480 students, close to 300 staff; a total capacity, taking social distancing into account, of around 300. But it’s even more complicated than that. Some of her students do not have use of their arms, and it may not be safe for them to wear masks. Some of her students are not toilet trained: How was her staff to safely change their diapers? About a third of her students cannot walk unassisted. To avoid putting them on elevators, she is trying to schedule them all for the ground floor. Every morning at 7:45, she has a Zoom meeting with her four assistant principals. Every Monday, she has a Zoom meeting with her staff. Including them in all the planning has made her life easier, and kept her sane.

She showed me the small cluttered offices of her assistant principals, which face each other across a ten-by-ten-foot inlet in the main hallway. She planned to put in some bookshelves to block off the space from the hallway, turning it into a small classroom to make room for more students.

“What will happen to the assistant principals?” I asked.

“I don’t care!” said Tremblay. “They have laptops.”

We talked about the decision to reopen the schools. Tremblay said she was glad it was not her decision to make. I asked if she was scared, and she said anyone who isn’t scared hasn’t been reading the news. She herself is 49 and has asthma, which would qualify her for a medical exemption, but she does not intend to take it. “My responsibility here is too great,” she said. “Though I may be deluded when I say that.”

We walked into the hallway. The building is relatively new. Unlike most city schools, it has a central hvac system. Still, the hallway felt stuffy. Tremblay and I were both wearing masks, and I was enjoying talking to her, but I wanted to get outside. I thought: What are we doing? Are we really going to stuff our kids into these child warehouses, endangering them, endangering their teachers?

I asked Tremblay if she would make the school go all remote if it were entirely up to her. She thought about it and said no. There are students at her school who have trouble with basic motor functioning; in the absence of the services and instruction they receive at P.S. 721K, she fears they may be regressing. “Too many kids need to come in,” she said.

And there it was — the dilemma facing every school, every teacher, every parent. And it hasn’t changed since March.

*This article appears in the August 3, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!

*This story has been updated to reflect that the city is using the positivity rate from confirmed tests, not an estimate of the overall infection rate, to determine if schools can reopen.