This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

When Trayvon Martin was killed, we were with the Grandmas — my mother and her mother — sitting in different rooms of the apartment the four of us shared. Trayvon Martin was 17, and my daughter was 2, about six months away from a diagnosis of developmental delay and hearing impairment. She played with a miniature family of figurines on the floor as footage of Sybrina Fulton and Tracy Martin flickered on our television screens. I assumed she was engrossed and oblivious simply because she was a toddler. I did not know the news reports weren’t entirely reaching her ears, or that communicating clearly with each other would become a yearslong challenge.

It wouldn’t have mattered, even if I’d known. Even if she’d been a little older and I’d already begun the long process of looking to her for cues about what I should teach her and when, I would have had no intention of telling her that night why the matriarchs of her household paced back and forth and wept. I intended to shield her from the pervasiveness of racial violence for as long as I could. I wanted her to know the insular happiness Black children can only be ensured in households where they are safe and loved.

This country prizes Black children’s precocity — insists on it, even, much of the time. This is true when the stories are positive: When, for example, a Black high-school senior is accepted into every Ivy League school in the nation, or when a Black second-grader raises enough money to eradicate student lunch debt at their elementary school. But it’s just as true when the stories are more harrowing: When, for example, a little Black girl chants, “No Justice, No Peace” after the police kill another unarmed man, or when a young Black boy sings an original composition about just wanting to live and it goes viral. In each instance, the child’s exceptionalism is applauded. Look how singularly focused they are. Look how aware of the world and how strong.

It is quite commendable when children courageously engage in direct action alongside their parents. I fully understand why a mother would want to apprise her child, as soon as possible, of what it’s like to grow up Black in America. We’re all told that the “next generation” will be the one to right the world we’ve wronged. Even if that is possible and true, I am not interested in any precocity that requires my daughter to sacrifice what’s left of her insular happiness and take on a heroism I hope she’ll have her whole adolescence and adulthood to hone.

Of course, this isn’t entirely up to me. When you are Black, even if you are a small child, you do not have to leave home for the police to barge in, guns drawn, and shoot without even a simple verification that they’re raiding the residence they intended.

Were that ever to happen to us, as it did to Aiyana Stanley-Jones in 2010 — the year my daughter was born — and as it did to Breonna Taylor, just months ago in March, none of my efforts to shield my daughter would amount to much. But unless something like that does happen, I am still the only one of us who needs to be worried about it.

This has long been my parenting philosophy. It’s something my daughter’s learning and hearing differences have taught me, as I’ve had to temper my own hasty expectations. She learned to speak, read, write, and reason at her own pace, not one I set or tried to accelerate for her. At first, I felt at odds with other families, comparing our academic and social benchmarks with theirs, wondering what I needed to do to “catch up.” But my daughter has always been her own person. I have never succeeded at hastening her progress, and in retrospect, I am sometimes ashamed that I’ve even tried.

She has always set our pace, no matter the destination. I know that if I want her to become aware of and engaged in the politics of race in America, I can take all the time I need, all the time her comprehension of those complexities allows. I can explain what racism and police brutality are without feeling like we need to mobilize as soon as I’ve gotten the words out. There is no reason to rush to raise her with a heightened awareness of the harm that awaits us outside our walls.

It should not be a badge of honor to know at an early age how much your homeland hates you. I am fortunate that no outside circumstance has already forced that knowledge upon my child. I’d be hard-pressed to do it myself prematurely. She will learn it soon enough. This country will show her better than I can tell her.

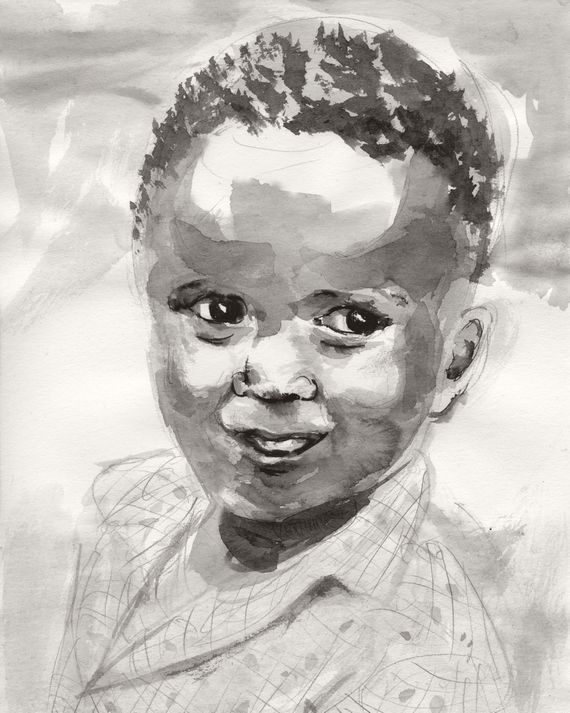

Eight days before a Ferguson police officer killed Michael Brown and left his body lying uncovered for hours on the street, my daughter’s father and I celebrated her fourth birthday by driving up to Sesame Place in Pennsylvania. When the artist at the face-painting booth asked what design she wanted, she answered with confidence belying her still-limited grasp of language: “I tiger.” After she waited patiently for her face to be airbrushed in orange-and-black stripes, we bought her a bubble gun. Soapy orbs encircled her for hours.

That was the only sort of shooting she knew.

Four months later, a police officer in Cleveland killed Tamir Rice while he wielded a toy gun of his own. He was 12. He was shot two days after my 34th birthday, and all I could do to mourn him was write. I wrote to him, as though I were writing to my daughter. I wrote what I was not yet ready to tell her, what I knew she would not yet understand, what I was in no hurry to translate into an age-appropriate introductory lesson.

Six months after that, in April 2015, in the city where we lived then, Freddie Gray was killed in police custody. Six Baltimore cops were charged, but half were acquitted. The others saw their charges dropped altogether. I left my daughter at home in the care of the Grandmas while I attended and covered his funeral. The luxury of leaving my daughter, ensconced in love and unaware of an imminent uprising, wasn’t lost on me.

On August 1, the same year, less than ten minutes from our apartment, Baltimore County police shot Korryn Gaines through her locked front door. Her 5-year-old Kodi was shot, too. He lived. She didn’t. That day, my daughter turned 6.

My daughter’s entire childhood has been marked by news reports of racial violence. I could list far more of them and tell you exactly where she was in time, age, and development when they occurred. How I and the other adults around her engaged, protested, or mourned them largely escaped her notice. That was by design, and I don’t regret it.

Two months from now, my daughter will be 10. In the middle of March, her school closed because a lethal new virus required us to self-quarantine. That virus was statistically more likely to hit the households of my daughter’s predominantly Black peers, her Black principal, and the Black teachers and staff she saw every day. Suddenly, environmental and medical racism were concepts it made sense to introduce. I could ease them in, along with reminders about hand-washing. I could tell her that America has long assumed its Black citizens are impervious to pain.

Then, as I was just growing accustomed to finding the right words for that, George Floyd was killed in Minneapolis and the world outside yet again erupted in nationwide protests against police brutality. This time, I told her what happened: A white policeman knelt on the neck of a Black man, unarmed and detained, until that Black man died. And now, people were marching to demand that it won’t happen again.

“Remember the civil rights movement?” I asked. Thinking I needed a very basic point of reference, I thought back to an animated film she’s watched a few times, Our Friend Martin. “When Dr. King marched against discrimination?”

My daughter gave my shoulder a placating pat. “Not be mean or anything,” she whispered, “but I don’t think Dr. King’s plan is working. Maybe we need a new plan?”

I wondered if she noticed my shock. I tried to quickly cover it. Clearly I’d underestimated her awareness. I looked at her in awe and with curiosity. Her expression was inscrutable but patient, as if to say, “Mommy, catch up.”